Pan American Airway’s Aviation Mission to China: Part 4

By Eric H. Hobson, Ph.D.

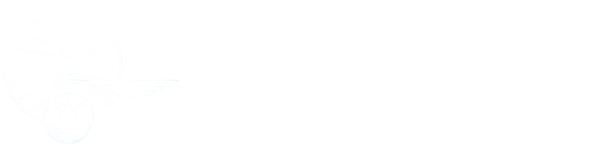

Manila banquet in October 1936 with Harold M. Bixby in the foreground (Courtesy Jon Krupnick Collection)

Manila banquet in October 1936 with Harold M. Bixby in the foreground (Courtesy Jon Krupnick Collection)

October 1936 was intense for Harold Bixby, Pan American Airway’s (PAA) Special Representative to the Far East. He learned in July that PAA’s inaugural transpacific passenger service would focus world attention on Manila throughout October as a publicity tour (10/7-24), a VIP tour (10/15-11/2), and the first passenger flight (10/21-11/4) came and went. He learned also that all Manila-end planning for publicity, housing, tours, parties, and meetings (business and political) fell to him.

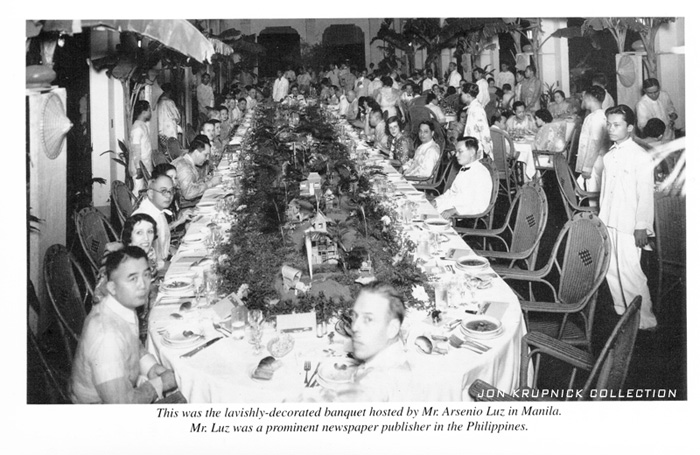

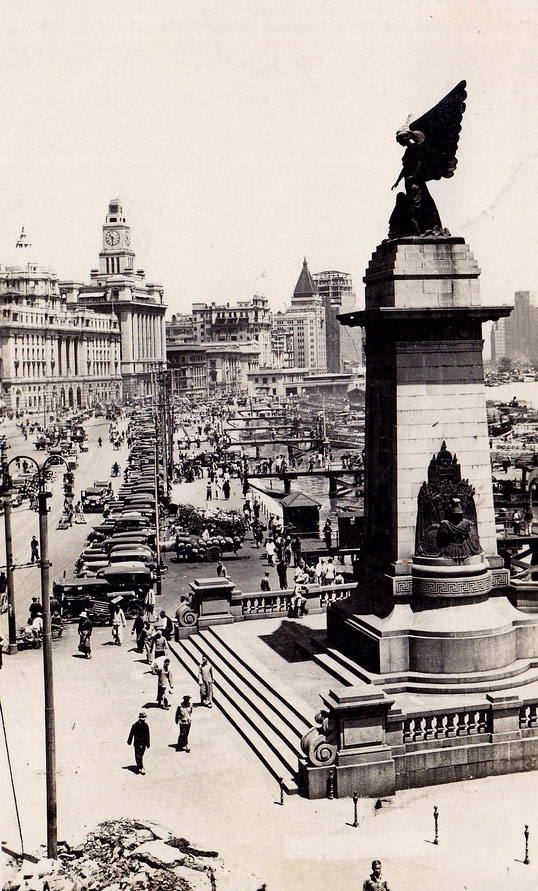

From the book "Pan Am's First Lady" by Betty Trippe - Oct 1936 36 Honolulu arrival celebration (PAHF Collection)

From the book "Pan Am's First Lady" by Betty Trippe - Oct 1936 36 Honolulu arrival celebration (PAHF Collection)

Although each flight was important, the second -- the Philippine Clipper (M-130, NC14715) that left Alameda October 15 -- was Bixby’s pressing concern. Captain J. H. “Pop” Tilton was bringing PAA President Juan Trippe and Board Chairman, Sonny Whitney (and their wives, Betty and Gee), PAA Directors Eddie McDonnell and Graham Grosvenor, and Bob Lord, Trippe’s secretary, on a transpacific-route dress inspection, cum corporate victory lap. California Senator, William McAdoo (with wife, Eleanor) and five publishing executives (Tom Beck, Roy Howard, Paul Patterson, Jimmy Stalhman, and Ed Swasey) were aboard as PAA guests.

Having flown the route recently, albeit without press fanfare or late-into-the-night dinners to distract him, Harold knew the group would reach Manila wrung out. Diplomatic protocol and company interests, however, demanded he schedule every Manila minute. Philippine President Queson’s invitation to a Palace party in Trippe’s honor was a must-accept, as was a U.S.-interests’ regional economic/military discussion with Major Dwight Eisenhower, standing in for General Douglas MacArthur. After these, Harold slotted requests as best he could. He also notified his wife, Debby, that the Trippes and Whitneys were coming to Shanghai (the Bixby family’s current home) and asked her to arrange appropriate reception activities and to schedule spouse entertainment.

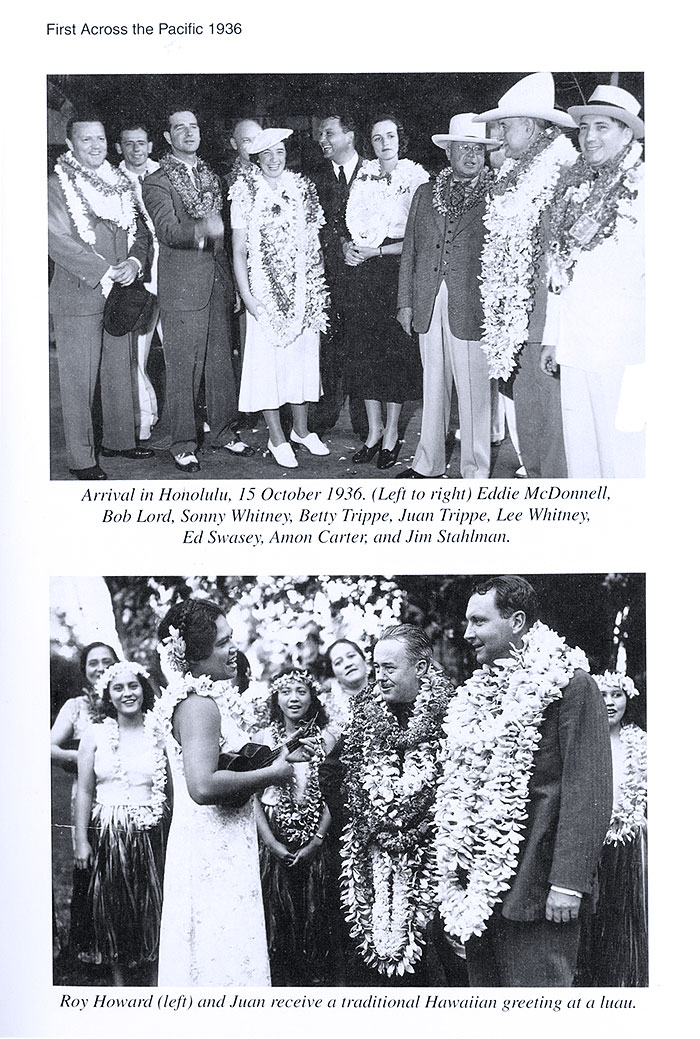

The Bund Shanghai, c. 1935 Postcard (Wikimedia)

Throughout Wednesday the 21st, Bixby finalized local arrangements, coordinated Shanghai scheduling with Debby, and tried yet again to secure Hong Kong landing privileges, all the while tracking the Philippine Clipper toward Manila. Hong Kong remained a loose end, even though Trippe’s travel plans included a Hong Kong goodwill stop; still, as he drove out from Manila to PAA’s Cavite terminal to greet the Philippine Clipper, Harold was certain that everything else related to the coming week’s activity was set.

The Manila Hotel c. 1930s (Eisenhower Library.gov Collection)

After settling his guests to rest in the Manila Hotel before a series of lavish receptions and dinners, Harold’s staff passed him word that the Hawaii Clipper (M-130, NC14714) had left Alameda on schedule with PAA’s first paying transpacific passengers. Bixby gave Trippe the news, even though neither man would greet Captain Musick when he landed on the 27th. They would be in China dealing with PAA’s future aspirations.

At 3:30 a.m., Friday the 23rd, The Philippine Clipper crew sat at breakfast anticipating the day’s two-hop flight and watched their passengers stumble in after a long night out. Betty Trippe recalled that scene as, “an hilarious affair. Some of our fellow passengers were still very high and some of our new Filipino friends came by on their way home from the party to say good-bye.” “The crew,” she added, “seated at one end of the table, were, in contrast, serious, rested, and businesslike.” Regardless of his passengers’ state of sobriety, Captain Tilton left Manila on time at 5:45 a.m.

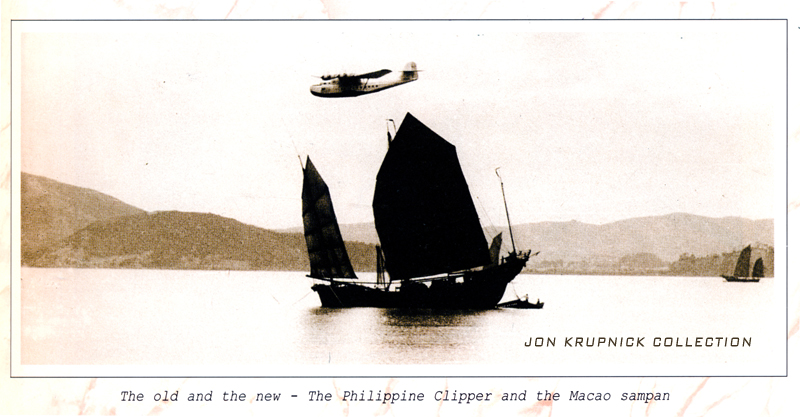

M-130 Philippine Clipper over Macao (Courtesy Jon Krupnick Collection)

Betty Trippe (back left) & Juan Trippe (in hat) deplane at Macao, Courtesy Frances Bixby/Pan Am Historical Foundation collection

Hours later, the more sober and slightly rested assemblage sat for an ornate lunch with Macao’s Governor, after which they flew twenty-minutes across Kowloon Bay to Hong Kong, where Bixby had secured one-time landing rights a mere forty-eight hours earlier. That night’s dinner at the Government House went late, adding to Betty Trippe’s mounting exhaustion; however, it paid off as her husband charmed Hong Kong officials in side-bar conversations and opened doors to PAA that had been shut before. By the end of the day’s travels, Betty was a Harold Bixby fan. He was, she wrote in her diary, “a great addition to our party.”

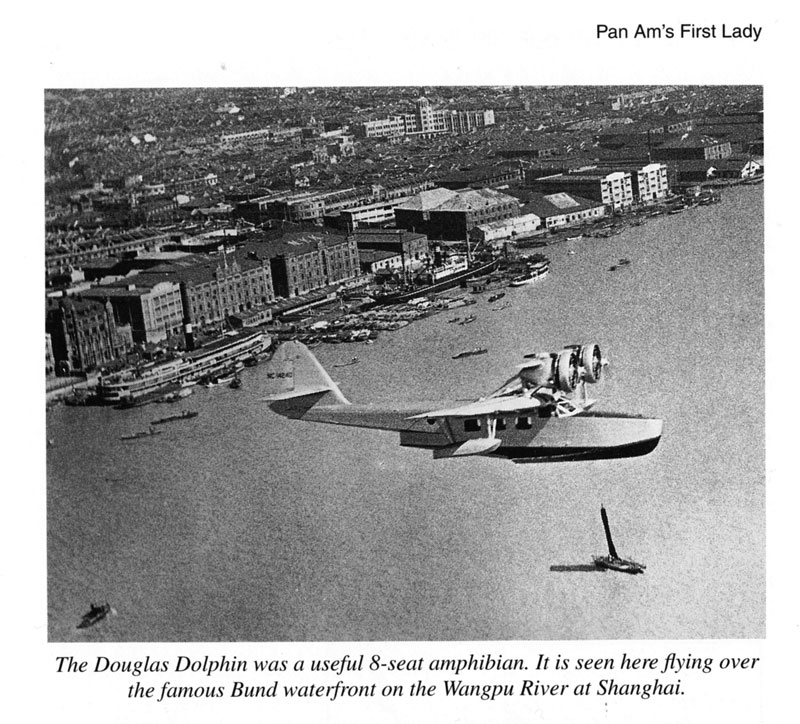

CNAC Douglas Dolphin over Shanghai from the book "Pan Ams First Lady" (PAHF Collection)

CNAC Douglas Dolphin over Shanghai from the book "Pan Ams First Lady" (PAHF Collection)

The PAA group divided the next morning (Saturday, Oct. 24). Eight persons reboarded the Philippine Clipper, while the rest watched the seaplane begin to retrace the transpacific route east to California. With the Martin M-130 gone, Harold led the Trippes, Whitneys, Howard, and Patterson to an idling China National Aviation Corporation (CNAC)-liveried Douglas Dolphin, and introduced the airline’s Chief Pilot, American Chili Vaughn. As Captain Vaughn prepared to take off, Harold encouraged everyone in earshot to follow his lead and nap during their one-thousand-mile, four-stop, flight to Shanghai.

Art Deco- style Park Hotel, built in 1934, overlooked the Shanghai Race Course and was the tallest building in Asia for over 30 years.

Among the crowd awaiting their arrival eight-hours later was Debby Bixby. After meeting her guests and welcoming her husband home, Debby guided the group to the Park Hotel, and then on to a dinner hosted by Shanghai’s Mayor. The following day (Sunday, October 25), while Harold rousted their male guests for day-long business meetings, she let Betty Trippe and Gee Whitney sleep in. Then, she took the two wives to a quiet lunch followed by a silk shopping excursion in Shanghai’s old city.

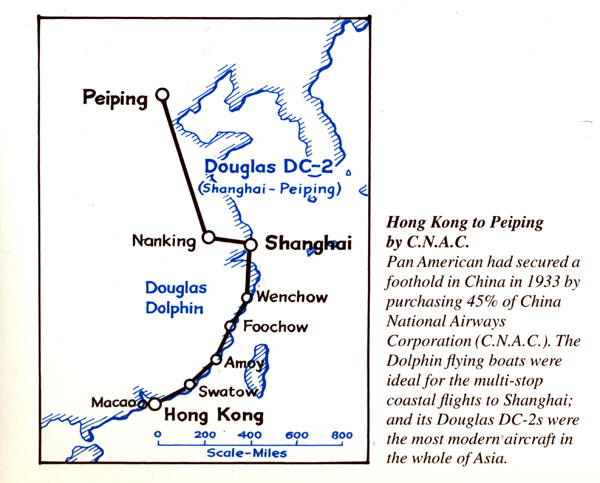

Debby Bixby’s day as a corporate hostess ended late as she bade dozens of men and women goodnight after a roof-top tea dance she organized to introduce PAA’s leadership to CNAC’s top executives and spouses. Now Debby Bixby could catch her breath. Harold, however, faced another early boarding call, because his schedule included a five-day fact-finding tour over much of CNAC’s routes. By the time Bixby returned to his own bed in Shanghai, Harold had flown to Peiping, on to Nanking, back through Shanghai, and south down China’s coastline to Hong Kong. The schedule was booked solid: meetings with the U.S. Ambassador and equally important Chinese officials, sightseeing, and multi-course meals at each stop. This itinerary allotted few hours for sleep each night.

CNAC survey trip map Credit: R.E.G. Davies (PAHF Collection)

CNAC survey trip map Credit: R.E.G. Davies (PAHF Collection)

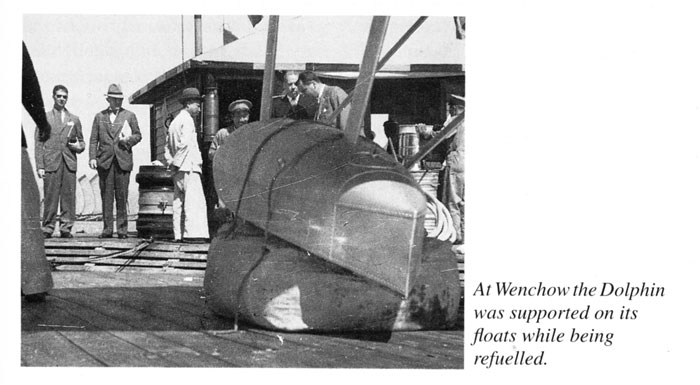

Bixby (center) waiting for Dolphin refuel at Wenchow (PAHF Collection)

As they said goodbye to Bixby in Hong Kong mid-morning, Tuesday, November 3, 1936, the Trippes had flown 3,000 miles on CNAC equipment, met most of the employees, and left China impressed by the company’s efficiency, professionalism, and profitability. A few months later, Harold received a congratulatory letter from his friend Charles “Slim” Lindbergh. “I have always felt that Pan American was very fortunate to have you in charge of their interests in China,” he wrote. “I believe that during the last year or so they have realized that fact more fully. The last time I spoke to Trippe he was greatly impressed with the work you have been doing.”

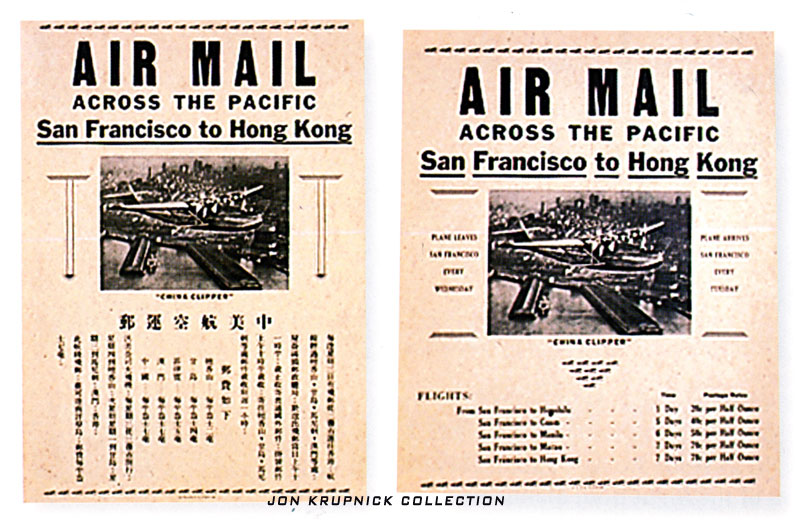

By the start of 1937, Harold Bixby and PAA were confident about PAA’s future in Asia. After having lobbied the British Government and Hong Kong colonial officials for more than three years, Harold finally secured landing rights at Kai Tak Airport. As he and Trippe had predicted, PAA’s decision to use the more-welcoming Macao as its transpacific route terminus rather than capitulate to British demands turned the tide. PAA’s Macao presence generated such economic (and social status) pressure that Hong Kong’s business community demanded that the Governor ignore Imperial Airways demands for reciprocal rights in Manila. On January 19, 1937, Harold inked a five-year contract with Hong Kong for PAA transpacific airmail and commercial services.

Hong Kong airmail poster (Courtesy Jon Krupnick Collection)

Trippe now had the US-to-Shanghai route he dreamed of when he sent Harold Bixby to China four years earlier, and on April 28 the Hong Kong Clipper (S-42B, NC16735) landed in Hong Kong, bringing the first airmail from Alameda. By the middle of May, passenger service was initiated, allowing PAA passengers direct access China. Leaving the PAA seaplane that brought them to Hong Kong, passengers transferred to CNAC aircraft to finish the final leg in their PAA ticketed Alameda-to-Shanghai journey.

Debby Bixby picked up a still-warm .50 caliber machine gun slug from her living room floor on Saturday afternoon, August 14, 1937. Outside, small-arms fire and automatic rat-a-tat punctuated the nerve-fraying rhythm of artillery-shell and aerial-bomb concussions. Less than a mile away on Shanghai’s Central Post Office roof, Harold watched Chinese Air Force bombers dive at the Japanese warship, Idzumo, anchored in the Whangpoo River firing into the city point-blank. Inexperienced pilots released bombs early -- most fell into the river, but several exploded in refugee-packed Nanking Road between the upscale Cathay Hotel and the equally plush Palace Hotel.

Japanese cruiser Idzumo in Shanghai (Wikimedia)

After shuttering the PAA-CNAC office, Harold entered blood-soaked downtown streets and walked home. Writing in Topside Ricksha, (his self-published, limited-print memoir, circa 1938), Harold remarked, “Did you know that it’s impossible to walk through blood? It is extremely slippery. I had to make a detour. Pieces of people were hanging on the telephone wires.”

At 279 Rue Charles Culty, a villa in Shanghai’s more-secure French Concession, Harold told his family to pack one small suitcase each because it was time to leave. He would work with U.S. Embassy staff and pull every string among his Chinese and international contacts to evacuate Debby and the girls. Harold also needed to evacuate the company’s personnel -- pilots, mechanics, managers, radiomen, meteorologists -- and these employees’ dependents. He wanted everyone out of immediate harm’s way, along with essential CNAC assets. Their exit was not guaranteed; thousands of Chinese nationals and foreigners had the same goal.

The evacuation target was Hong Kong, eight hundred miles south. Already, CNAC DC-2 aircraft were shuttling maintenance equipment, spare parts, and fuel reserves, even as the Chinese Government officials commandeered CNAC aircraft and crew for flights into China’s interior, making them targets for Japanese fighter planes.

A typhoon lashing China’s central coast on August 17, and a partially honored twenty-four-hour truce between the Chinese and Japanese militaries, gave the British and U.S. navies a window to evacuate European and American nationals (women and children only). At 10 a.m. Harold loaded his family and many PAA/CNAC employee wives and children onto a US Navy tender that headed down the Yangpoo River to the outer harbor where the SS President Jefferson was anchored.

Instead of an anticipated ten minute ride, Debby Bixby and her daughters sat in the refugee-packed boat for two hours tossing through rough seas trying to reach the President Jefferson (1). Eventually, Harold received word in his PAA/CNAC office from the Dollar Steamship Line that the refugee-packed ship had sailed for Manila, Philippines, and, not knowing when or how he would follow, he turned his attention to a growing list of problems.

Eight days later (August 25, 1937) on board the Dollar Line’s SS President Pierce en route to Hong Kong with dozens of PAA/CNAC personnel, Harold was exhausted as he wrote to PAA Vice President Stokley Morgan, “These are trying days. Bombs bursting around town – no transportation – no stenographic assistance – no sleep with guns roaring all night – airplanes constantly overhead with anti-aircraft guns firing at them. Employees of CNAC and PAA asking what to do, where to go, and how to get paid.” After detailing how he had dealt with these challenges, Bixby ended the six-and-one-half-page, typed, single-spaced letter with a frank appraisal: “I believe we have followed a wise course under all the circumstances. At least we have not embroiled our American Government in any mess and we have kept PAA out of any embarrassing situation.”

As he left Hong Kong Saturday August 28, 1937 to join his family at Baguio in the Philippine highlands and work out of PAA’s Manila office for the foreseeable future, Harold reflected on the chaos in Shanghai and on CNAC-PAA’s precarious position. This reality was not how Harold Bixby wanted his four-and-a-half-year China posting to end.

In the eight months since evacuating PAA/CNAC and his family from Shanghai, Bixby traveled constantly between PAA offices in Manila and Hong Kong to keep PAA’s Pacific operations and CNAC’s China operations going through increasingly difficult times. Away for weeks at a time, his family kept up with him via a steady stream of airmail letters postmarked from as far away as Calcutta, India, French Indochina (Vietnam) and Chungking, China. Even in the face of pessimistic forecasts about China’s future in the face of Japanese encroachment, Harold worked to adjust PAA’s Asia footprint, finalizing the US-to-New Zealand route and working toward a route to Singapore and beyond.

Sikorsky S-42B Pan Am Samoan Clipper at Pago Pago (Courtesy Jon Krupnick Collection)

Sikorsky S-42B Pan Am Samoan Clipper at Pago Pago (Courtesy Jon Krupnick Collection)

1938 began on an up-beat note when Captain Musick, flying the Samoan Clipper (S-42B NC16734) left Aukland, New Zealand carrying the first load of airmail on what would become a regularly scheduled route (2). And, as bad as things had looked for CNAC in August, it was still flying most of its China schedule and managing, somehow, to turn a profit. Harold credited his friend, William Bond, CNAC’s operations manager, for the airline’s resilience, and told Juan Trippe so in a March 31 phone conversation. At the end of the call, Trippe told Harold that he wanted him in PAA’s home office permanently.

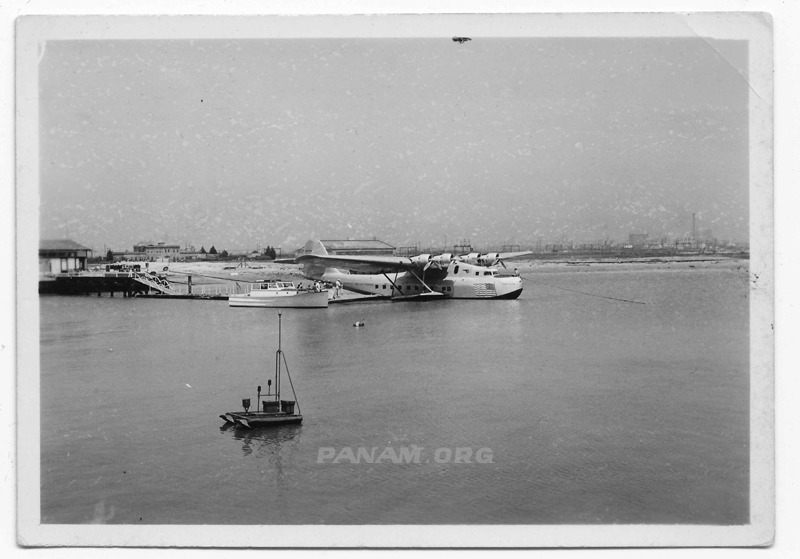

Richard Rhode photo M-130 Hawaii Clipper Alameda w Panair launch (PAHF Collection)

Richard Rhode photo M-130 Hawaii Clipper Alameda w Panair launch (PAHF Collection)

Harold, Betty, Catherine and Hebe Bixby boarded the eastbound PAA M-130 Hawaii Clipper at Manila, April 15, 1938 under the command of Captain Charles A. Lorber, ending Harold’s posting as PAA’s Far East Representative. Unlike his 1936 record-setting Manila-New York City transpacific and transcontinental trip, Harold and family stopped in San Francisco after 57.3 flying hours, to join daughters Frances and Elisabeth who left Manila in February. Harold was now PAA Vice President responsible for the Pacific Division and Alaska Divisions -- everything PAA related from Anchorage to Auckland, San Francisco to Saigon. After resting in San Francisco, visiting family and friends in St. Louis, the Bixby family headed to New York City where Harold settled into a Chrysler Building office.

Harold Bixby & Debby on Boeing 707 prototype in 1955 (Bixby Family Collection)

Harold Bixby died November 19, 1965, having retired from Pan Am in 1955 as Administrative Vice President and Board Member. Writing from Paris upon receiving the news, Charles Lindbergh wrote to Debby Bixby about the depth of the four-decade Slim and Bix friendship: “Bix was among the top great of the men I have known, and I say this not simply because of my gratitude to and friendship for him. He had a quality, strength, and balance of character seldom encountered in this world – never encountered as he combined those elements.” “Debby,” he finished, “I can write no more. I feel too deeply.”

A year later (Aug 6, 1966) Lindbergh wrote to apologize that neither he nor Anne could attend a memorial service held for Harold in upstate New York. Lindbergh explained that such an event was not necessary for him anyway, because “there is no need of a service to keep Harold Bixby’s memory fresh in my mind. Such a man leaves an impression on the minds of his friends and associates that the passage of time does not eradicate – in fact the impression in many ways grows keener.”

Footnotes:

1. The President Jefferson’s captain found 350 refugees aboard a lighter designed to carry 50 persons alongside his ship in the midst of a tropical storm. He waved the boat away, afraid the overloaded boat might damage his ship; however, he relented, and, later said the boarding of these refugees as “the most dangerous transfer at sea he had ever witnessed.”

2. Ten days later (Jan. 11, 1938), the Samoan Clipper, exploded off of Pago Pago, killing Captain Ed Musick and nine colleagues.

Works Cited:

Barrett, Benjamin C. The Spirit Behind the Spirit of St. Louis Harold M. Bixby. Troy Book Makers, 2019.

Bixby, Debby. The H.M. Bixby in China 1934-1938. Self-published pamphlet (circa 1953-55).

Crouch, Gregory. China’s Wings. Bantam Books, 2012.

“Harold Bixby, a Chief Supporter of Lindbergh’s `27 Flight, Dies” November 20, 1965.

Krupnick, Jon E. Pan American’s Pacific Pioneers: A Pictorial History of Pan Am’s Pacific First Flights 1935-1946. Pictorial Histories Publishing Co., 1997.

Trippe, Betty Stettinius. Pan Am’s First Lady: The Diary of Betty Stettinius Trippe. Paladwr Press, 1996.

Acknowledgement:

Thanks to Ben Barrett for publishing “The Spirit Behind the Spirit of Saint Louis, Harold M. Bixby” which compiles materials from his grandfather’s life, for answering a host of my questions, and for providing photos to enliven this article.

Read excerpts & purchase Ben Barrett's book now available at:

https://www.thespiritbehindthespiritofstlouis.com/