HAWAII’S GIFT TO THE WORLD

The story of modern surfing has a lot to do with the influence of one man, a native Hawaiian named Duke Kahanamoku, and also maybe a little to do with Pan Am, the first airline to fly to Hawaii from the mainland.

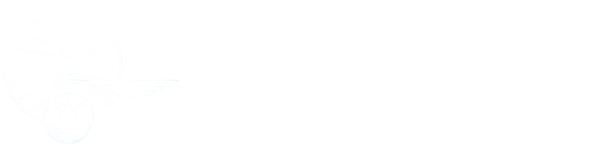

US Commemorative Stamp featuring Duke Kahanamoku & His Achievements, 2002 (Photo: US Postal Service)

Surfing History

This year’s Olympic Games in Japan are featuring something brand new – for the Olympics that is – the sport of surfing. It’s been a long time coming, but looking back into surfing history, it’s obvious that one man, Duke Kahanamoku, Hawaii’s foremost “Waterman” was in large part single-handedly responsible for spreading the awareness and popularity of this distinctly Hawaiian athletic pursuit to places far from his home in the Pacific. It grew out of the passion that Duke had for surfing, reviving popular interest in the “wave sliding” tradition — once the sport of Hawaiian kings — that had taken root in Hawaii’s early history. During the early 1900s before WWI, at the time when he was a young man in Honolulu, Kahanamoku’s enthusiasm for riding the waves, along with his strong community of fellow surfers, helped launch surfing onto the worldwide stage.

Sons of the Surf, a 1920s film from Internet Archive

As the sport grew over the years, by the 1960s, surfing was on a lot of peoples’ minds, in places that dotted the globe. By then, much had evolved in the way people rode the waves, compared to earlier times. For instance, the boards had morphed from giant 16 foot, 100+ pound wood planks to much shorter and lighter gear, with skegs (fins on the bottom). And the sport itself was even more dynamic, with surfers conquering giant waves that would have been impossible with earlier surfboards.

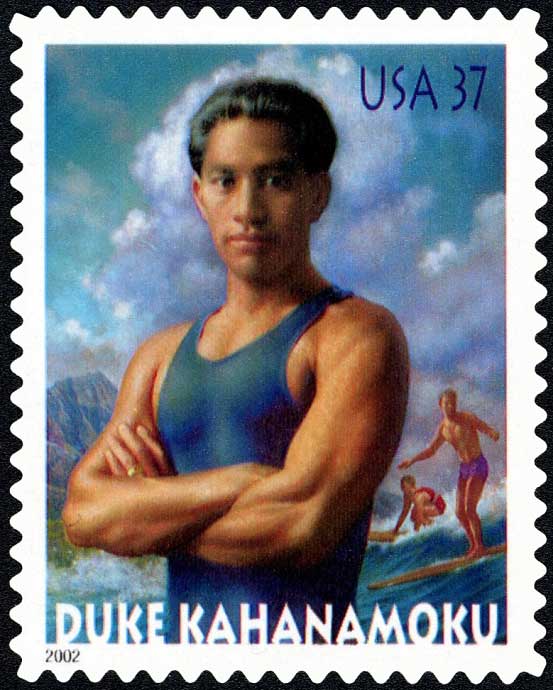

Woodcut print of “Hawaii, The Surf Rider” by Charles W. Bartlett, 1921 (Photo: Honolulu Museum of Art Collection, Wikimedia)

Pan Am & Hawaii

Back in the 1930s, when Pan American’s Clippers were still a new phenomenon over the Pacific, Hawaii was central to the company’s operation. It was an essential stop on the way to and from Asia. And for the flying boats of those days, it was just within reach from the mainland in California. The view of Diamond Head lit by the rising sun had to be a very welcome sight to Pan Am travelers after the long overnight flights from Alameda.

Pan Am Martin M-130 at Pearl City Hawaii (PAHF-Stan-Cohen-Collection)

Waikiki — where Clipper passengers and crew were put up to await their onward passage the next day — was an enchanting place for travelers to visit. By the time the Clippers flew scheduled flights to Honolulu, Waikiki had changed dramatically from the quiet village it had been, before the Kingdom of Hawaii turned into a territory of the United States. But the native Hawaiians who lived there maintained much of their traditional culture, despite pressures to adapt to the new imported ways of life that were increasingly growing up around them.

Duke Kahanamoku - Hawaii’s Waterman

Young Duke Kahanamoku was a son of Waikiki. His family had moved there when he was a toddler of three in 1893, the same year that an American-backed plan overthrew Hawaii’s Queen Lili’uokalani and monarchy. He was the son of a Honolulu policeman, also named Duke Kahanamoku, with family connections to Hawaii’s royal lineage. (“Duke” was a given first name, and not a royal title or nickname, however.)

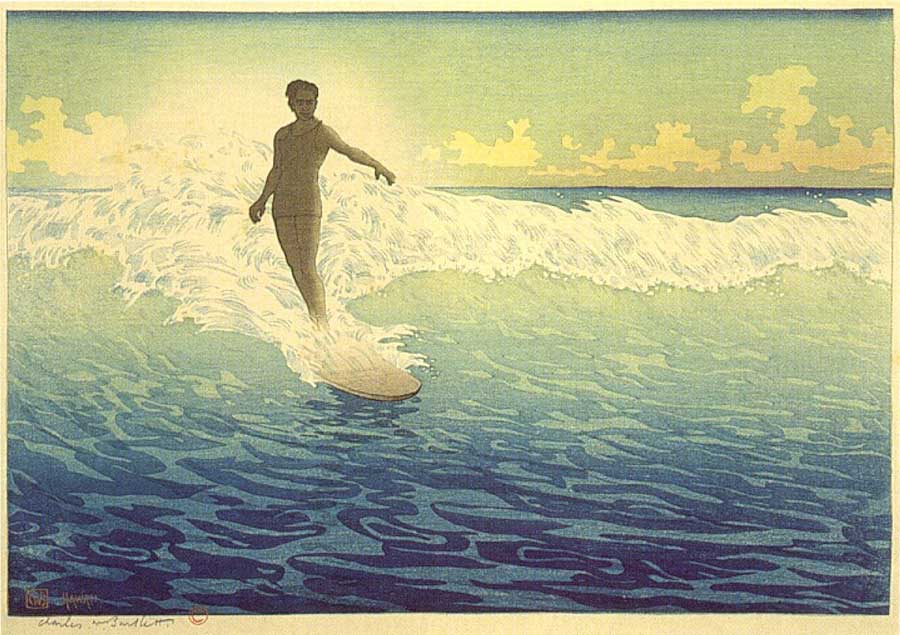

Duke Kahanamoku (3rd from right) and his Troupe (Photo by Frank G. Carpenter, 1921.US Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division).

Duke grew up near and in the water, swimming, surfing, and paddling outrigger canoes. He learned to surf using the traditional koa wood long boards that had carried Hawaiian royalty on the waves of Waikiki in times past, just like a great many other young Hawaiians. But Duke proved a superlative natural athlete, providing a direction in life that would carry him far across many waters.

Duke’s Career as an Olympic Swimming Champion

In 1911, entering a swim meet in Honolulu and astounding the race organizers by swimming 100 yards in 55.4 seconds, he beat the world record at that time by 4.6 seconds. This feat opened a door for Duke, and the next year he qualified to join the US team at the 1912 Olympics in Stockholm.

Duke returned home to Hawaii from the Olympics in Sweden with gold and silver medals, which he did again during the next Olympics in Antwerp in 1920. No games were held during WWI. But he wasn’t finished: at the Paris games in 1924, Duke (now age 34) won a silver medal.

Duke Kahanamoku (R) with Johnnie Weissmuller, another American Gold Medal Swimmer, at the 1924 Paris Olympics (Photo: Bettman Collection, Wikimedia).

Duke the Ambassador

Duke wasn’t just a talented athlete, he was a natural diplomat too, welcomed wherever he went.

Between Olympic appearances, Duke traveled widely. He went to Southern California in 1912, and to Australia two years later, demonstrating and teaching Hawaiian surfing – spreading the pastime that would grow into a global fascination with the sport. He also discovered new opportunities in the 1920s, and as a celebrity, was offered background parts and character roles in Hollywood. But equally important were his friendships with local movers and shakers in L.A., such as members of the Los Angeles Athletic Club.

Duke with his surfboard in Los Angeles, 1921 (Photo: Los Angeles Times Archive, Wikimedia).

The Intersection of Pan American and Duke’s “Lifelines”

By the 1930s, he was back in Hawaii and his popularity spurred him on to get elected as Sheriff of Honolulu, a post he held until 1960. From then on, he was often called on to preside as an ambassador for Hawaii — known as the “Ambassador of Aloha”.

Duke Kahanamoku (at far left) and the crew of the Pan American Clipper, April 17, 1935. Hawaii Governor Poindexter on far right (Photo courtesy Jon Krupnick Collection).

Duke was on hand to welcome the very first Clipper Sikorsky S-42 flying boat to land at Honolulu on April 17, 1935 with Ed Musick piloting. Along with Hawaii Governor Poindexter, Duke was there for the heroes’ welcome, standing with Ed Musick and his crew of the “Pan American Clipper” during their arrival celebration. It was the beginning of a long association between the famous Hawaiian and Pan American Airways.

During the flying boat era and beyond, Pan Am recognized Duke’s celebrity status and began to highlight him in promotions, creating a natural association between the airline and Hawaii that lasted for three decades into the 1960s.

Duke with fellow passenger Ignatius Fealy before boarding a Pan Am Clipper flight , 1937 (Photo: Pan American Air Ways, January 1937, courtesy Dr. Roger Easton).

Duke would have many occasions to meet, interact, and become friends with Pan Amers and it’s more than likely that his love of surfing rubbed off on the new acquaintances.

Captain Horace Brock, in his great book “Flying the Oceans: A Pilot’s Story of Pan Am 1935 - 1955” (Jason Aronson, New York, 1978) described the experiences of Pan Am crews when they arrived in Honolulu:

“After a few hours rest, we would get up and go down to Waikiki to swim and chat with the beach boys. The most famous surfer was Duke Kahanamoku… [They would] take any of us out, for free, through the surf on their 16-foot hollow surfboards, and back in behind them, on the steepest part of the waves just beyond the curl."

Brock’s experience was repeated regularly, and not only by him. Dozens of other Pan Am crew who passed through Hawaii also learned from Duke’s skills and willingness to impart surfing expertise. Their experiences were undoubtedly shared with an ever-widening circle of people, far beyond the Hawaiian Islands.

Clip of Waikiki Scenes from the Pan American Airways Film, “Transpacific” in the late 1930s (PAHF Film Collection).

Duke and his surfing community continued to welcome and coach all newcomers to the sport. It didn’t hurt that Pan Am’s pitch to potential customers at that time enticed them with a thrill they’d never get anywhere other than on a beach at Waikiki.

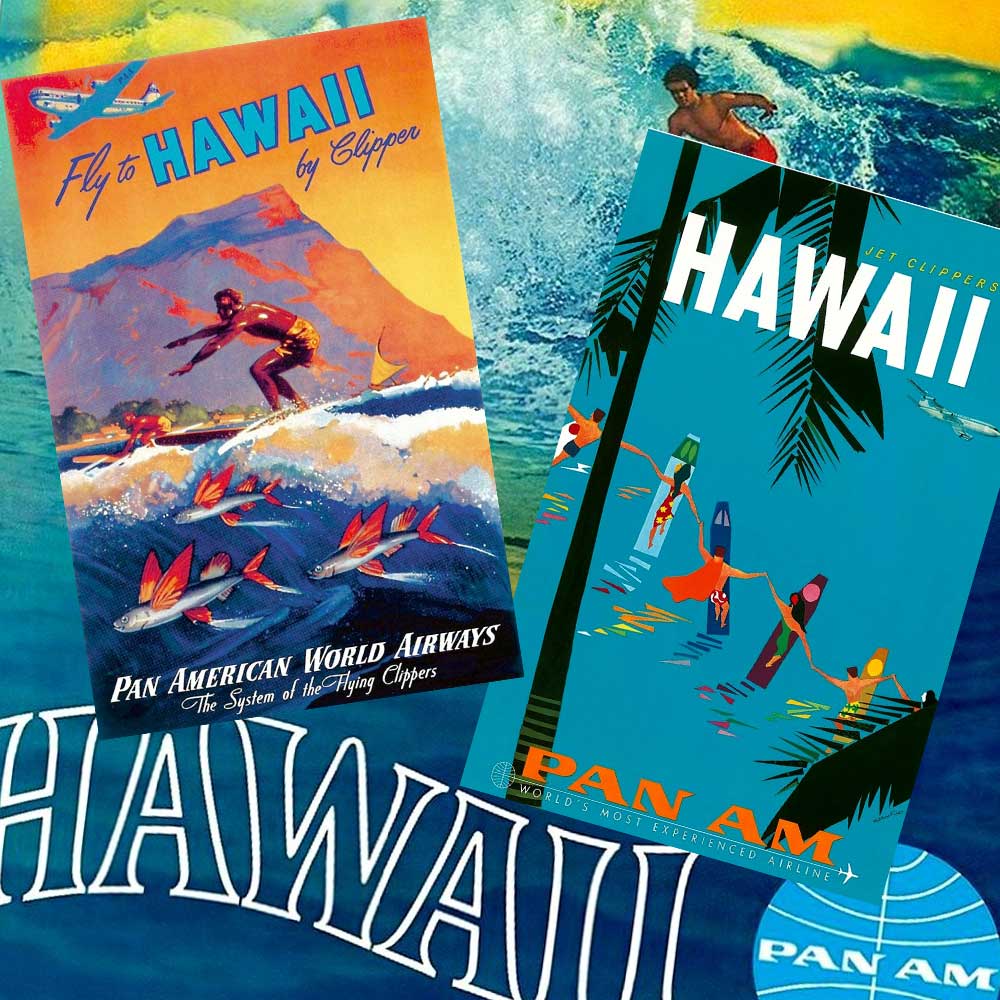

Pan Am Hawaii Promotional Posters, 1940-1960 (PAHF Collection)

As Duke’s interests and visits took him to places far beyond Hawaii’s shores, Pan Am was there to provide the means for him to get there. In 1961, to celebrate new jet service to Scandinavia, Pan Am took Duke and his brother, Sargent, along with a large group of Hawaiians to Scandinavian capitals to promote service to Hawaii. At the time it marked a fond return to Stockholm for Duke, where he had begun his Olympic career as a gold-medal swimmer just under half-a-century before.

Duke passed away in 1968, but what he had started in Hawaii went on to become a global phenomenon. His legacy lives on, and after more than a century, Duke Kahanamoku’s dream of surfing as an Olympic event has finallyr reached the Olympics --Tokyo 2020.

Duke on the Beach with His Surfboard, 1921 (Photo: Los Angeles Times Archive, Wikimedia).