JANUARY 1933

Scroll down to read

Five January 1933 posts

JANUARY 2, 1933

"Happy New Year - Pan Am Service Slogans"

(1) “211 of the 302 employees stationed at this port” ("Pan American Air Ways," April 15, 1931). (2) Dinner Key staff posing atop & around Pan Am's Sikorsky S-40 Caribbean Clipper that was delivered Nov. 1931 (PAHF/Jahncke Collection).

(1) “211 of the 302 employees stationed at this port” ("Pan American Air Ways," April 15, 1931). (2) Dinner Key staff posing atop & around Pan Am's Sikorsky S-40 Caribbean Clipper that was delivered Nov. 1931 (PAHF/Jahncke Collection).

"Pan American Air Ways," March, July and October 1932 issues, had carried page footers related to service, safety, and airmail. The July issue encouraged readers to send in “better ones” for consideration, promising that “Acceptable slogans will appear in subsequent issues.” October issue’s slogans contained 30% repeats, suggesting a tepid response from Pan Am’s front lines. Perhaps Pan Am employees just shared their ideas on the shop floor.

By 1933, corporate sloganeering was gone without comment in the year’s first issue of “Pan American Air Ways.”

PAA SERVICE SLOGANS FROM 1932:

• “Every New Prospect You Turn Into A Passenger Is Good For 5 More”

• “The Public Judges Your Worth By The Courtesy You Practice”

• “ ’Via Pan Amercan’ Means Fastest, Most Comfortable, Most Dependable Way To Travel”

• “Alertness And Enthusiasm Always Produce Big Results”

• “Politeness Pleases Passengers”

• “Pan American’s High Reputation Is Built On Attention To Details”

• “How Many Passengers Recall Pleasantly Your Thoughtful Courtesy?”

• “One Thing Done Right Is Worth A Dozen Good Intentions”

• “Passengers Pay For Comfort – Nobody Likes To Feel Cheated”

• “Only Your Cooperation Can Make Pan American A Complete Success”

• “`On Time As Usual,’ Means That No Detail Has Been Neglected”

• “Tomorrow’s Good Record Depends On Today’s Perfect Performance”

• “There’s No Such Thing As Being `Nearly’ Efficient”

• “Acceptable Service Speaks For Itself”

• “Teach More People To Say, `As Reliable As Pan American`"

• “Air Travel Makes Short Trips Of Long Ones”

• “Every Passenger Is A Life Entrusted Your Care”

• “A Man’s Value To Aviation Is Not Greater Than His Dependability”

• “The Greatest Action Is Composed Of Small Details”

• “Aviation Needs More `Career Men’ And Fewer Jobholders”

• “Excellent To Meet All Emergencies Well – Better To Prevent Them”

• “Courtesy, Comfort, And Dependability Build Passenger Traffic”

• “Your Opportunities Grow With Pan American – Build Traffic”

• “There Is No Substitute For Attention To Details”

Sources: “Pan American Air Ways,” (March 15, July 15, & October 15, 1932).

JANUARY 3, 1933

"Cash in Hand, Ready to Fly"

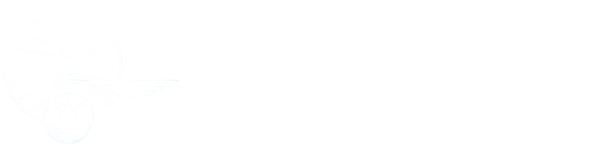

(PAHF Collection): Top to Bottom. Pan Am Sikorsky S-38 (l). Pan Am Sikorsky S-40 (r). Pan American Airways Ad, “A Trip Abroad in 2 Hours," c. 1930s (bottom photo).

(PAHF Collection): Top to Bottom. Pan Am Sikorsky S-38 (l). Pan Am Sikorsky S-40 (r). Pan American Airways Ad, “A Trip Abroad in 2 Hours," c. 1930s (bottom photo).

Fare discounts to Havana, Cuba and Nassau, Bahamas pushed demand 40% over 1932’s holiday season.

Knowing this, Don Singer expected heavy traffic Tuesday morning January 3, 1933 as he opened Pan Am’s Dinner Key base. Don scanned flight manifests to see midmorning arrivals from Havana and Nassau 100% booked, and 13 tickets sold for the day’s Havana flights – still, walk-up passengers were a given. By midmorning, 39 people queued to fly to Havana, while across the Florida Straits, ticket agents faced a similar surge.

As "Pan American Air Ways" (p.19) reported, “all were accommodated,” but doing so required rapid adjustments because the day’s passenger load overwhelmed its equipment schedule.

Carl Dewey, flying the 38-seat Caribbean Clipper (Sikorsky S-40 NC81V) left Kingston, Jamaica at dawn for Miami via a Cienfuegos, Cuba refueling stop, then diverted to Havana and took on 33 passengers. Pan Am’s other S-40, American Clipper (NC80V), left Miami on its Miami-Havana-Miami route full as did the 20-seat Consolidated Commodore on the day’s Havana-Miami-Havana run.

A Commodore kept in reserve was pressed into service to Havana and a spare Sikorsky S-38 flew to Nassau and back. The Caribbean Clipper’s extra seats along with the spare Commodore allowed 125 passengers to return from New Year’s revels in Cuba’s capital.

Miami-Havana traffic demand remained high and Dewey’s one-off Havana diversion became permanent, adding seats between Miami and Havana. January 1933 volume was 50% higher than in 1932, as Pan Am moved 2537 passengers through Miami.

Source:

“Pan American Air Ways” (Vol. 4, No. 1, p.19), & “The Daily Gleaner” (Kingston, Jamaica) 1/4/1933, p.23.

JANUARY 16, 1933

“A Hard Day/Night Flight”

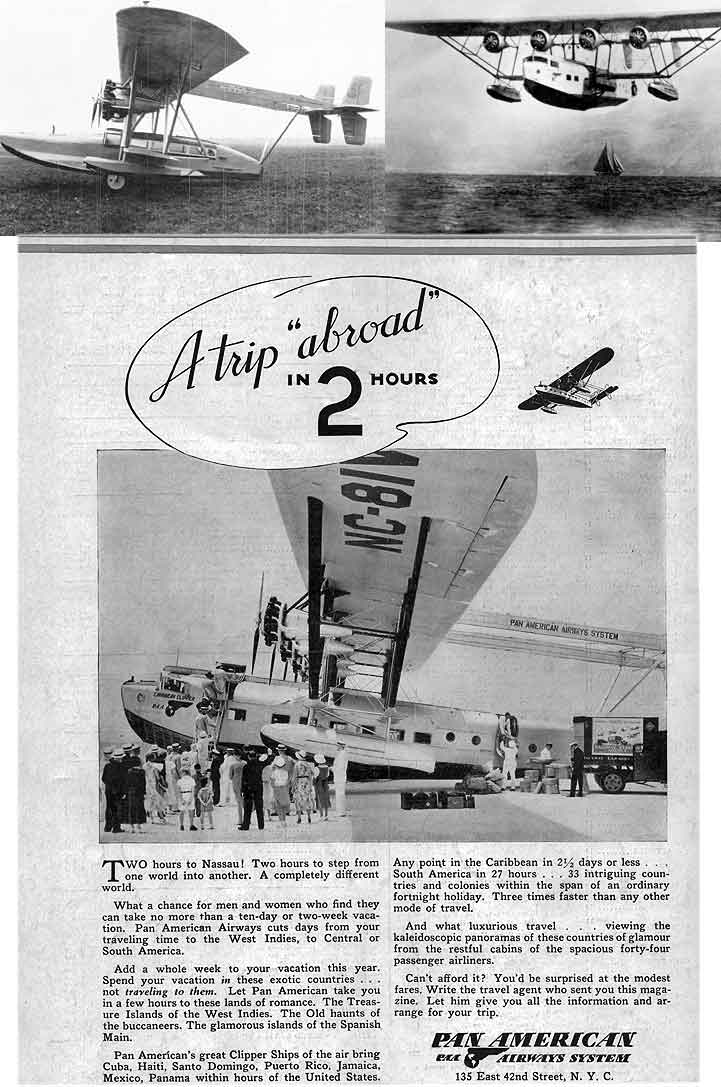

Photos: (1) "Consult this Map for Fastest Way to All Points in Latin America." Time tables, tariffs: Havana, Nassau, Mexico, Panama, West Indies, Central and South America, June 15, 1933. p. 4. (2) "Oldest and Newest Transport in Peru. Group of Llamas Visit Their Rival in Tranportation -- A Pan American Grace Tri-Motored Ford, Santa Rosa." From "Pan American Air Ways,' Vol. 4, No. 1, March 1933. p. 26.

Photos: (1) "Consult this Map for Fastest Way to All Points in Latin America." Time tables, tariffs: Havana, Nassau, Mexico, Panama, West Indies, Central and South America, June 15, 1933. p. 4. (2) "Oldest and Newest Transport in Peru. Group of Llamas Visit Their Rival in Tranportation -- A Pan American Grace Tri-Motored Ford, Santa Rosa." From "Pan American Air Ways,' Vol. 4, No. 1, March 1933. p. 26.

Pilot W. Smith and crew arrived in Lima, Peru late Monday, January 16 exhausted at the end of 16 hours and 10 minutes of flying that started 1,906 miles southeast in Mendoza Argentina. This flight was supposed to have left Mendoza Saturday afternoon, but storms, wind, fog and ice had closed the area’s only trans Andean route for 40 hours. Once Smith took off Monday morning, he pushed the PANAGRA Ford AT-5-C hard.

The scheduled northbound route had 8 stops (Mendoza – 112 miles – Santiago – 250 miles – Ovalle – 593 miles – Antofagasta – 446 miles – Arica – 40 miles – Tacna – 140 miles – Araquipa – 475 miles – Lima), including an overnight in Antofagasta, Chile, halfway between Santiago and Lima. This Monday each stop was just long enough to swap out mailbags and passengers while fuel was loaded and the cockpit windows cleaned, and Antofagasta was 1,000 miles behind at bedtime.

The report of Smith’s flight in "Pan American Air Ways" (4.1, p. 26) indicate neither his departure nor arrival times. Because the first leg (Mendoza to Santiago) threaded the 15,000 foot Uspallata Pass, Pan Am/PANAGRA policy limited these flights to daylight hours. First light in mid-January comes at 6:20 a.m. on January 16 in Mendoza, Argentina; full light follows in 28 minutes. Assuming Smith left Mendoza at 6:30 a.m., his Lima arrival was no earlier than 10:40 p.m., the last four hours and 10 minutes flown in the dark.

Smith’s efforts returned the route to on-time service and Tuesday’s northbound flight from Lima to Salinas, Ecuador left on time. Luckily for Smith and his copilot/mechanic/radio operator, the next southbound flight wasn’t until Thursday, January 19, so they could sleep in.

Sources & Photos:

•"Pan American Air Ways," Vol. 4, No. 1, March 1933. p. 26. https://digitalcollections.library.miami.edu/digital/collection/asm0341/id/40869/rec/1

•"Consult this Map for Fastest Way to All Points in Latin America." Time tables, tariffs: Havana, Nassau, Mexico, Panama, West Indies, Central and South America, June 15, 1933. p. 4. https://digitalcollections.library.miami.edu/digital/collection/asm0341/id/20443/rec/39

JANUARY 17, 1933

“PAA Moves Northeast”

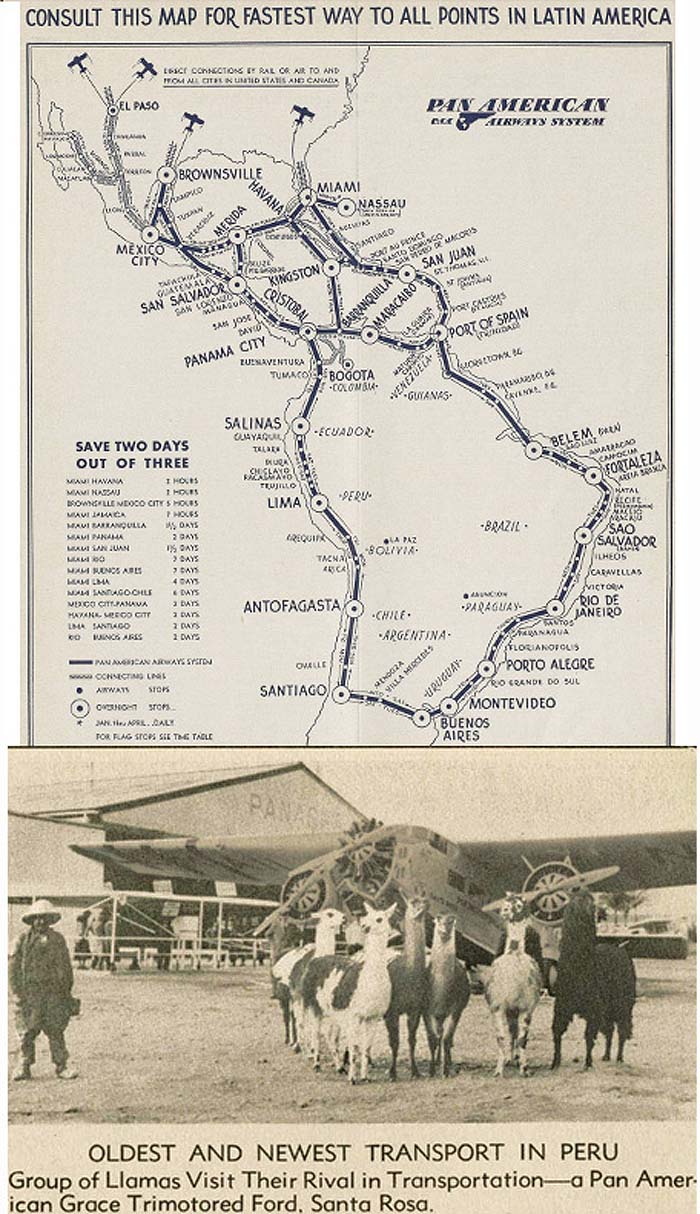

Photos by George Sioris, PAHF/Johnson collection. (1) Hangars at Port Washington, New York, c. 1937. (2) Sikorsky S-42 Bermuda Clipper at Port Washington hangar in 1937 after Pan Am began scheduled flights to Bermuda & transatlantic survey flights.

Photos by George Sioris, PAHF/Johnson collection. (1) Hangars at Port Washington, New York, c. 1937. (2) Sikorsky S-42 Bermuda Clipper at Port Washington hangar in 1937 after Pan Am began scheduled flights to Bermuda & transatlantic survey flights.

Having established the Caribbean and South America markets, Juan Trippe looked to Europe for Pan Am’s next expansion. The transatlantic market was well established and he had calculated profits available through subsidized U.S. Air Mail and passenger service. A few months earlier he had signed contracts for three Sikorsky S-42 and three Martin flying boats, both capable of crossing the Atlantic —at least on paper — using a series of refueling stops.

To support that plan, Pan Am had sponsored the 1932 Jelling Expedition to study Greenland’s weather; a 1933 continuation of that effort was planned, along with a transatlantic survey flight by Charles and Anne Lindbergh.

On January 17, 1933,to provide a base for Atlantic operations, Pan Am purchased a 12-acre lot on Manhasset Bay off of Long Island Sound. The purchase included piers and ramps, two hangers and other buildings constructed in 1929 by American Aeronautical Corporation as a test site for the Savoia Marchetti S-55 & S-56 amphibious aircraft that they were building under license.

The property would idle for four years because of British refusal to grant landing rights without reciprocal service (even though no British aircraft could serve the route). Thus, Pan Am focused on transpacific service before returning to activity at Port Washington in 1936. The Atlantic Division’s 1st transatlantic survey flight to Europe left Port Washington on July 6, 1937.

Source: Denise Duffy Meehan, “How Port Washington Gave Birth to Pan Am” Goodliving Magazine (1987), pp. 22-25.

JANUARY 23, 1933

“Flying Blind”

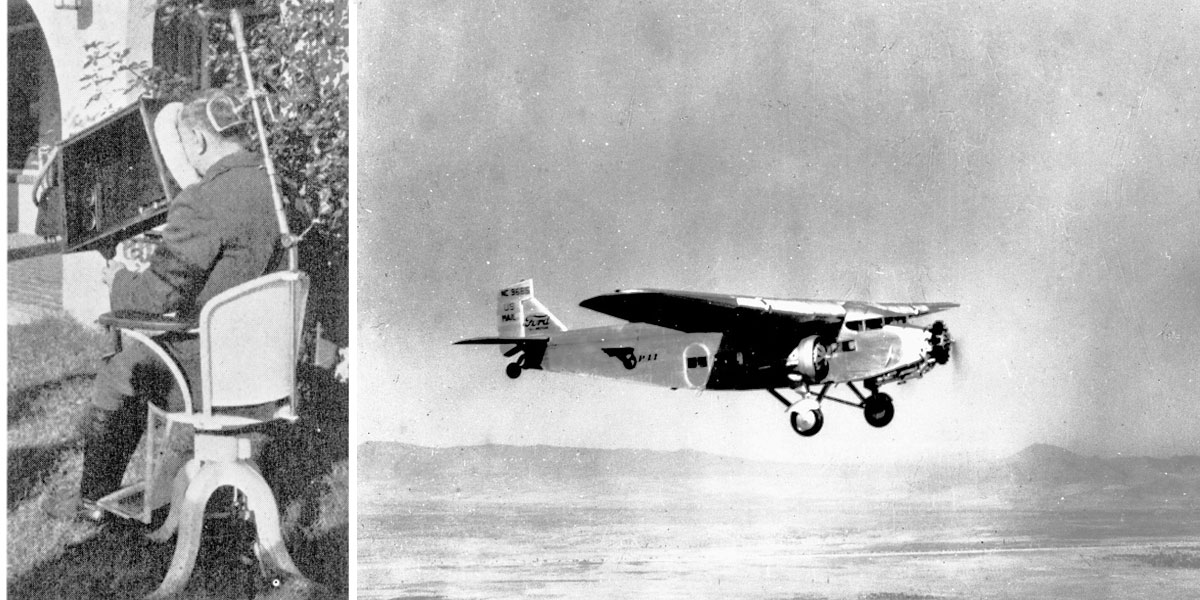

Left: Pan American Airways instrument flight training at Brownsville from Banning, Gene, “The Airlines of Pan American Since 1927," Paladwr Press, 2001, p. 100. Right: Pan Am Ford Trimotor in flight, c. 1930s (PAHF Collection).

Left: Pan American Airways instrument flight training at Brownsville from Banning, Gene, “The Airlines of Pan American Since 1927," Paladwr Press, 2001, p. 100. Right: Pan Am Ford Trimotor in flight, c. 1930s (PAHF Collection).

Pan Am faced the need to “fly blind” as soon as it bought out Compania Mexicana de Aviacion (C.M.A.) four years earlier on January 23, 1929. As "Pan American Air Ways" (4.1, p. 9) writers noted, CMA’s routes were the most challenging among all of Pan Am’s: … the “Tampico-Mexico City route … demand(s) from 5 to 90 minutes of blind flying daily.”

Aviation historian, Erik M. Conway, credits Pan Am as setting an unofficial industry baseline by establishing its own training program in Brownsville, Texas. Pilots rode the Jones-Barany chair-Ocker’s box combo to break their fly-by-feel confidence, then flew a blacked-out Fairchild FC-2 before training in multiengine aircraft. Conway notes, “Pan Am required a minimum of ten hours of instruction. It also required … recurrent training … and an hour of practice monthly … to keep pilots who did not routinely encounter blind conditions from backsliding after the training course and returning to dependence on their sense of balance.” (p.28) (Note: Pan Am’s major bases -- Miami, Brownsville, Alameda, CA, and, Port Washington, N.Y -- had a retrofitted Fairchild trainer.)