Transpacific Flight and the China Clipper:

The Technical Tasks

By John G. Borger, 1985

Note: John Borger was hired on as a Junior Engineer to work on the North Haven Expedition in 1935. He went on to serve Pan Am’s Engineering Department for many years, in a career that stretched well into the Jet Age. In this article he took a long fact-based look at what made the China Clipper the right airplane to manage Pan Am’s first transoceanic route – across the Pacific.

Fly passengers and mail across the Pacific in 1935-36? Many knowledgeable aviation people thought this to he highly questionable, if not impossible, when Pan Am announced plans early in 1935. The Pacific had been flown before, but only on one of a kind or stunt flights - certainly not on a scheduled basis. But Pan Am, led by Juan Trippe, proposed weekly trips to Manila and back, carrying payloads, and in full compliance with government safety regulations.

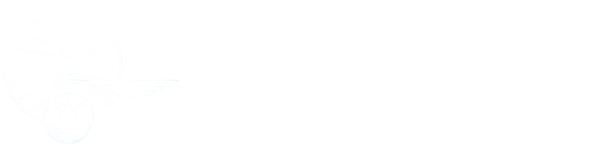

A contemporary ad of the day depicting the M-130, Cutler-Hammer Motor Control

A contemporary ad of the day depicting the M-130, Cutler-Hammer Motor Control

Today, when men have walked on the moon, when space shuttle trips have become almost commonplace, and the Pacific is being flown many times a day, it may be difficult to appreciate the technical tasks that confronted Pan Am 50 years ago. First, there was no air- plane that could fly the 2,410 miles from the U.S. West Coast to Honolulu carrying at least 800 pounds of mail plus six passengers, as the Post office was to require in the Air Mail Contract. Second, there were only three dots on the map between Honolulu and Manila - 5,300 miles. Landing and refueling facilities would have to be established. Thirdly, flight and ground crews would have to be trained. Navigation methods accurate enough to permit finding a two by four mile coral atoll would have to be developed. Communications would have to be improved so that an airplane could be in constant touch with at least two stations on each flight leg, night or day, fair weather or foul. Methods for forecasting enroute weather would have to be developed, even though reports from ground stations were few and far between, and shipping lanes bore much to the north of the track from Midway to Manila.

Experience with earlier transpacific flights had not been encouraging. Army Air Corps Lieutenants Maitland and Hegenberger had flown from Oakland to Honolulu in 1927, followed by Smith and Bronte, who ran out of fuel over Molokai. Only two of the starters in the Dole Trophy Race in 1927 made it to Honolulu, the other six didn't. Others had tried, turned back or were lost. One Navy plane was forced down and sailed over 500 miles before rescue; others made it later. Kingsford Smith had made the flight enroute to and from Australia. Charles and Anne Lindbergh had flown "North to the Orient" along the Aleutian chain. Post and Gatty had crossed far to the north on their round the world flight. Pangborn and Herndon, after several attempts, had flown from northern Japan to Washington State. And Amelia Earhart flew from Honolulu to Oakland early in 1935. No one had flown from Honolulu to Manila. All these flights were made in special planes with extra fuel tankage, with overweight takeoffs. As flown, none could have qualified for transport airworthiness certification.

Hawaii Clipper at Wake, Courtesy of PAHF Rhode Family Archive

Not only was it extremely doubtful that rights could be obtained to land in Russian Siberia and Japan, but the Lindberghs had found that Aleutian weather could be severe, and quite unpredictable. So Pan Am selected the longer southern route. This went from San Francisco Bay to Honolulu, 2,410 miles; Honolulu - Midway, 1,380 miles; Midway - Wake, 1,260 miles; Wake - Guam, 1,560 miles; Guam- Manila, 1,600 miles; total 8,210. Landing rights for British owned Hong Kong were to come later. Prevailing winds were expected to be easterly over most of the route, so return trips would probably take longer than outbound.

Trippe had anticipated the need for an airplane capable of making long nonstop flights. Pan Am wrote aircraft manufacturers on June 26, 1931 requesting proposals for airplanes able to carry transocean payloads. Only the Sikorsky and Martin companies responded. Contracts were signed on October 1, 1932 with Sikorsky for 3 S-42 airplanes, and with the Glenn L. Martin Co. for 3 M-130's later in 1932. The China Clipper, an M-130, was the first airplane that met the requirements. In 1935, the U.S. domestic airlines had just absorbed 10 passenger Boeing 247’s and 14 passenger Douglas DC-2's; both were normally operated on flights of 300 to 500 miles. The famous DC-3 made its first flight after the China Clipper returned from Manila.

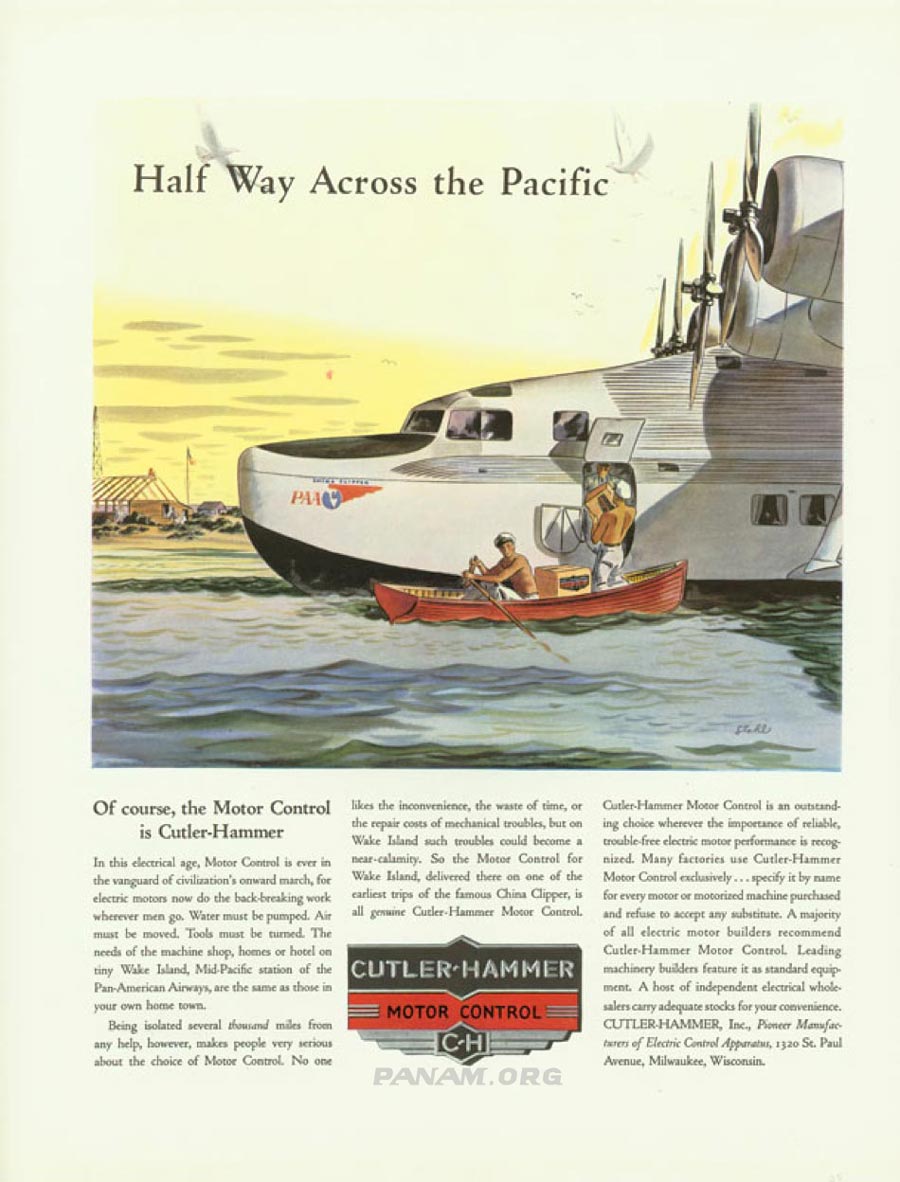

Delivered late in 1934, the S-42 had 28 passenger seats, (S-42A's and - B's: 32), and range of slightly more than 1,000 miles. It was not a true transocean airplane. The second S-42, the Pan American Clipper, was stripped of most of its seats so more fuel tanks could be installed, and operated overweight to make Pacific survey flights.

The Sikorsky S-42, Courtesy of R.E.G. Davies - Author, and Mike Machat - Illustrator

It flew first to Honolulu on April 16-17, 1935, returning on April 22-23. Then beyond to Midway in June, to Wake in August and to Guam in Oct. Only mail was carried east of Honolulu; company personnel and cargo, plus some mail, were carried to the other islands.

The China Clipper proved to be the answer; tests showed it exceeded original requirements. Designed to meet specifications prepared with Pan Am, three M-130's were built by Martin at Middle River, Maryland. The China Clipper was delivered on October 9, 1935, the Philippine Clipper on November 14, and the Hawaii Clipper not until March 30, 1936, because the bay at Middle River froze over before post testing refurbishment could be completed. President Glenn L. Martin supervised the program, together with L.C. Milburn, Vice President, B.C. Boulton, Chief Engineer, L.C. McCarty M-130 Project Engineer, and Ken Ebel, Chief Test Pilot. Chief Engineer Andre Priester headed Pan Am technical participation, assisted- by his staff, and advised by Col. Lindbergh. Capt. Edwin Musick and a Pan Am crew conducted acceptance flights.

First M-130 to be built: The Hawaii Clipper, at the Martin Factory

To digress for a moment to explain the challenges faced by designers of a long range transport airplane, they must try to achieve the best combination of high lift and low drag (high L/D), lowest engine fuel consumption, high propeller efficiency, and best ratio of fully loaded weight to weight with empty fuel tanks. The latter ratio usually is influenced most by low empty weight. The airplane must be able to take off within a reasonable distance at that fully loaded weight, cruise at as high a speed as can be justified economically and at comfortable cruising altitudes, and land within a reasonable distance at not too high a speed. There are many other considerations, including crew and passenger accomodations, suitable stability and handling characteristics, cabin heating and ventilation, service systems, emergency equipment stowage, etc.,etc.

The M-130 was the largest commercial airplane yet built; only the German DO-X and one or two other one-of-a-kind designs were bigger. Delivered with a. maximum takeoff weight of 51,000 pounds (later increased to 52,250), it was powered by four of the earliest Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp engines, rated at 800 horsepower (later 830, then 950). Thousands of Twin Wasps were built during World War II; some are still in operation on DC-3A's. M-130 wing span was 130 feet, hull length 91 feet. Fuel capacity was 4,080 gallons: two 100 gallon wing tanks, two 950 gallon seawing tanks, and two hull tanks totaling 1,980 gallons. Fuel had to be pumped from the lower tanks to the wing tanks, which fed the engines.

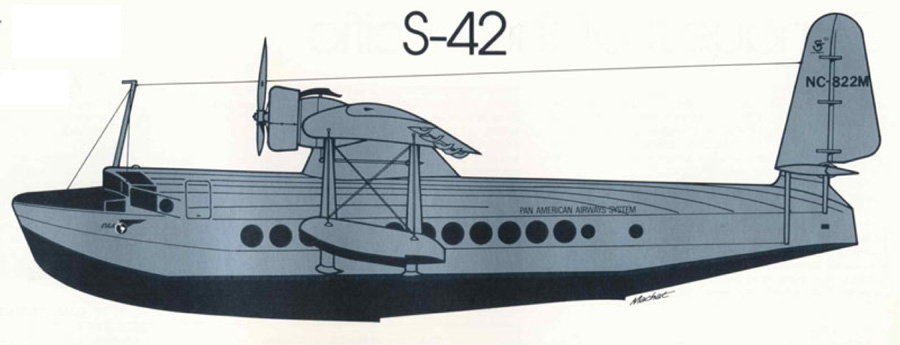

There were 36 seats in the cabin; 24 in three compartments could be converted into 18 berths, the remaining 12 were in a lounge/dressing room. On mainland - Honolulu flights, usually less than 10 passengers could be carried; sometimes only 4 or 5.

Some seats often were removed to reduce weight. There were four basic crew stations: Captain, First Officer, Radio Operator and Flight Engineer. One passenger compartment was converted to provide a table and instruments for the Navigator; two berths and two seats were retained here for crew rest. Three or four more flight crew members were aboard for basic crew relief, and for training for future Pacific and Atlantic operations. Usually, one steward was carried.

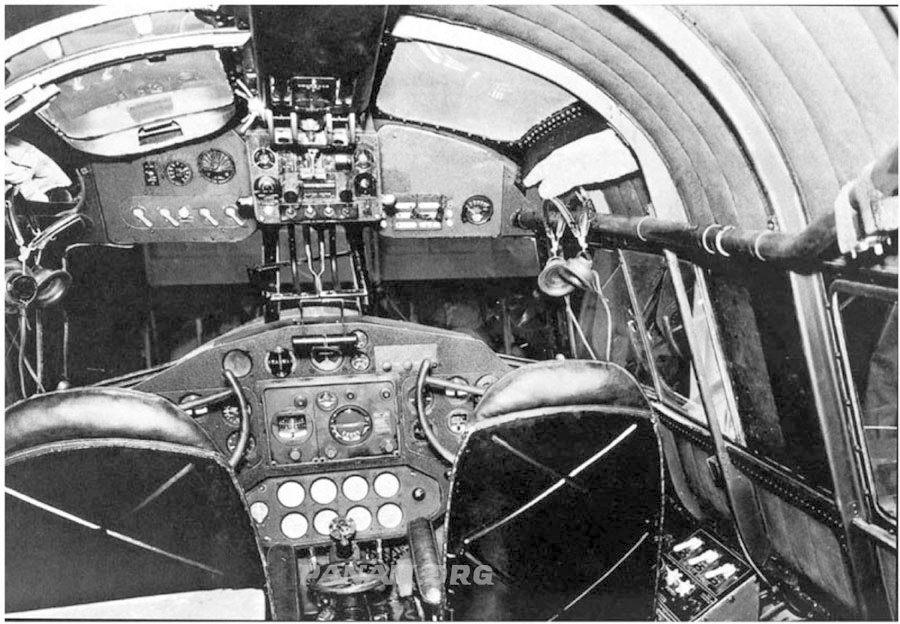

Photo: Flight-Engineer-in-cabane

Caption: The Flight Engineer’s station in the cabane

Price of each M-130 was $417,200.

The contractual obligation to carry 800 pounds of mail plus six passengers, their baggage, food and water added up to a payload of 2,300 pounds. (A B-747 freighter can carry more than 230,000 pounds) When carrying this payload, the China Clipper had a range of just over 3,500 miles. This was later increased to 3,750, through engine and airframe improvements. From these absolute ranges must be subtracted allowances for reserve fuel and headwinds, so the 3,500 miles becomes equivalent to West Coast - Honolulu capability against an average 21 miles per hour headwind. (Pan Am required that sufficient fuel be loaded for forecast flight time plus six hours.) Average cruising speed was 130 miles per hour. West of Honolulu, where flight legs were shorter, speeds were 5-10 miles per hour faster. Normal cruising altitudes ranged from 8,000 to 10,000 feet.

M-130 cutaway Illustration, courtesy PAHF Rhode Family Archive

Externally, the China Clipper appeared less cluttered than earlier flying boats. To keep propellers above the water, the high wing configuration was necessary. The wing-hull connection was made through a streamlined structure faired from the cockpit; this was called the cabane. An innovation on American flying boats was the use of seawings instead of wing tip floats to provide lateral stability on the water. They also provided fuel tankage. While claims were made that the seawings augmented wing lift, this was at least balanced by an increase in drag. In operation, seawings were preferred over tip floats. Wings, seawings and tail were externally braced by struts and tie-rods. Structural design had not yet progressed to a level where designers could rely on fully cantilevered high wings, which could produce less drag. This was one of the last airplanes built without wing flaps. But the structural design of the M-130 was outstanding. In 1936, transpacific flights were made at takeoff weights more than twice empty weight. This had been a long-standing goal for aeronautical engineers, and was to be exceeded only by the Martin Mars until the jets arrived.

Aerodynamically, the M-130 was good, but not outstanding. The China Clipper was 10-15 miles per hour slower than the earlier S-42. Lift/drag ratio was only a little over 12, so the superior range performance was achieved- more by the ability to carry more fuel, lower engine fuel consumption and better propeller efficiencies. Engine specific fuel consumptions were probably the lowest yet measured in flight, reaching minimums of about 0.41 pounds per horsepower per hour. Fuel consumption on Alameda-Honolulu flights averaged 126.6 gallons per hour for the first year. The then-new 87 octane gasoline was used.

Top and bottom of the hull were covered with corrugated aluminum alloy sheeting. This contributed to strength, but was detrimental to drag. Martin pioneered the use of integral fuel tanks, which have become standard on virtually all airplanes today. Sections of the seawings and hull were sealed off to form tanks.The cabin floor was also sealed, so it effectively became a double bottom for the hull. All control surfaces and the trailing edge of the wing were fabric covered.

Stations for the pilots were conventional, but raised about four feet above the main deck. Engine controls were overhead, as on most high wing airplanes. The Radio Operator's station was behind the pilots, on the right side. In addition to two receivers and controls for two transmitters on his table, there was a manually operated direction finder. The Flight Engineer sat further aft in the cabane. He had engine instruments, engine mixture and cowl flap controls and cabin heat controls, plus totalizing fuel flow meters. Communication between pilots and engineer was through an interphone that didn't work very well, and by an annunciator panel. The airplane was equipped with artificial horizons and an autopilot.

The M-130’s cramped flight deck

Radiotelegraphy was used because no radio telephone available had sufficient range. Transmitters and direction finders were built by Pan Am, and receivers modified from an RCA design. While there were fixed antennae on the airplane, a trailing antenna was used for long-range communications. This had to be reeled out and in by the Radio Operator. A spare was carried in case it broke off.

The passenger cabin, as in other flying boats, was divided into compartments to provide better flotation in case of hull damage. Furthest forward was the galley, from which the Steward was able to serve hot meals. Heat for the steam table was supplied by ethylene glycol (Prestone) fluid heated in engine exhaust stacks, and piped to the galley. This was probably the first full service galley on a transport airplane.

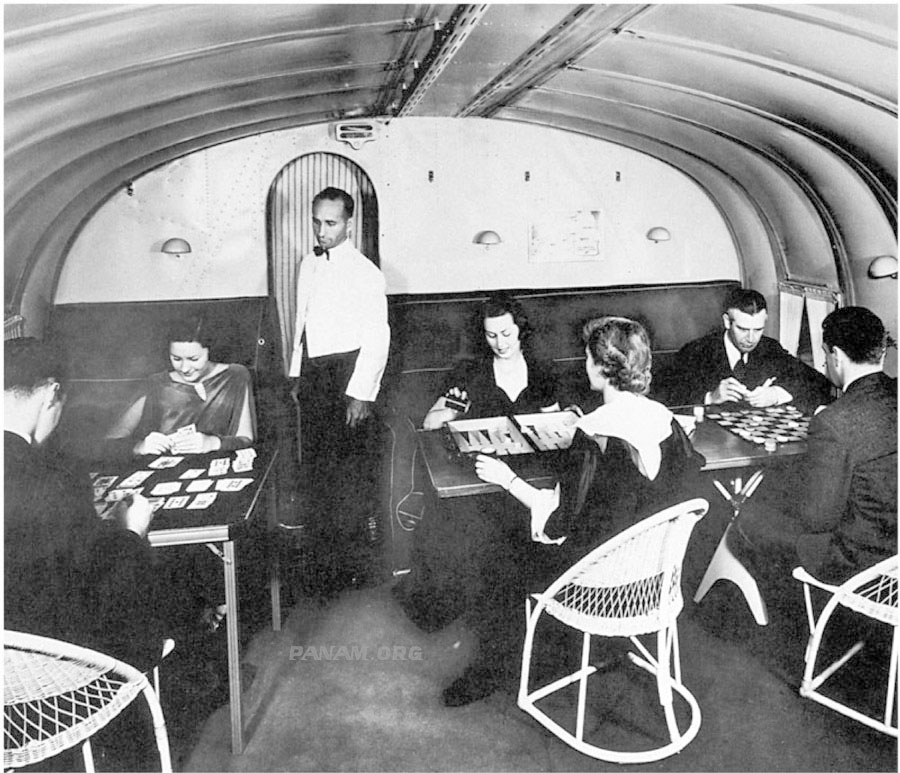

The next compartment was used by the Navigator and relief crew. On Alameda-Honolulu overnight flights, dinner and breakfast were served in the lounge. Passengers spent most of their waking time there, but smoking was not permitted on board because of proximity to fuel tanks. The cabin was unusually spacious for those days, and passengers could move about without disturbing other passengers. Aft of the lounge were two passenger compartments, each with eight seats convertible into three lower and three upper berths. Further aft were two small toilet compartments with cold running water; toilets were much like those in contemporary Pullman cars, with direct overboard waste disposal.

Passengers entered through a hatch in the top of the rear hull, down a stairway between the toilet compartments, and into the rear compartment. Mail was stowed in compartments forward of the galley, and baggage at the sides of the rear stairway.

Interior styling had been designed by Norman Bel Geddes.

The M-130 passenger lounge designed by Norman Bel Geddes

Cabin heat was also supplied by heated Prestone, but was rather marginal. No air cooling was available. The cabin was insulated, and not too noisy, certainly better than most contemporary airplanes. Both general lighting and individual reading lights were provided.

The crew divided flight duty time into watches, usually two hours on and two hours off. During the night, each pilot usually served one four-hour watch so off duty pilots could sleep. The Radio Operator was relieved by junior pilots, who were qualified to send and receive code messages. Relief crews usually included an Assistant Plight Engineer, although relief pilots could also man this station.

Three independent means of navigation were used. Every half-hour the Navigator reported the position of the airplane as determined by dead reckoning or celestial observation. Bearings were obtained from the radio direction finders at Alameda, Oahu, Midway, Wake, Guam and Manila to check diversions from the track. In dead reckoning, the Navigator evaluated airspeed, heading and estimated wind component to determine the position. To augment wind component estimates, a flare or glass chemist's flask filled with aluminum powder was dropped; drift was determined by measuring the angle between the flight path and the resulting spot on the water.

Celestial observation was accomplished by sighting the sun or stars through a bubble octant. Several sights had to be averaged to compensate for motion of the airplane. These sights were taken through an opened hatch above the rear stairway. Calculations were made by hand - there were no electronic calculators in 1935!

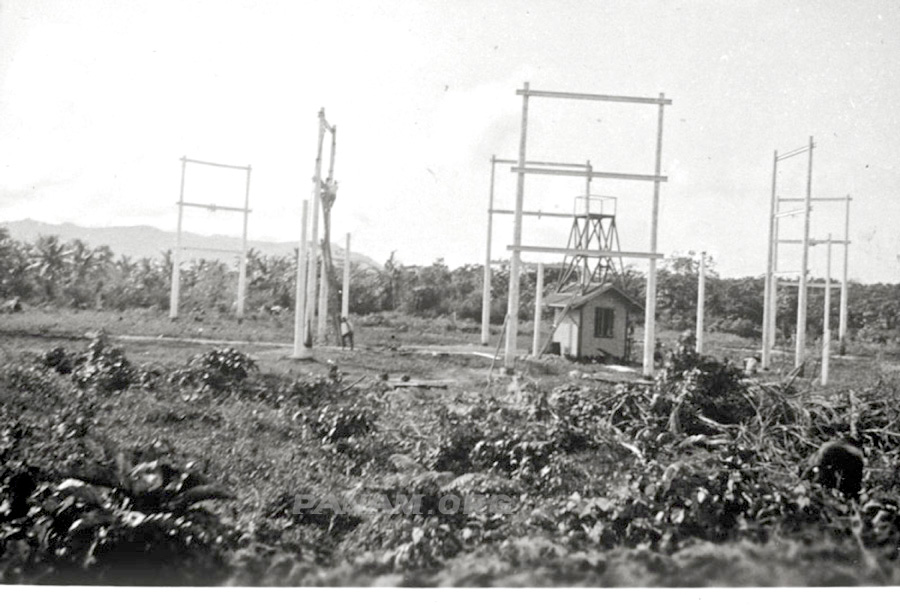

Much of the responsibility for the successful navigation record was attributable to the ground direction finders. These had been developed by Hugo Leuterritz of Pan Am, and were extremely accurate at ranges of 1,500 miles or more. But they were unable to determine distances, except through cross bearings. They were excellent homing devices. Radio Operators could also take cross bearings on ships with the airplane direction finder.

Long range radio direction finder under construction at Guam, courtesy W.G. Taylor Archive

Emergency equipment included a life jacket for each soul on board (SOB), portable oxygen, life rafts with more than enough capacity for all, rations and water for ten days on each raft, plus a hand-cranked radio, a fishing kit, flares, flashlight, knife, compass, matches, etc. A small water still was carried, as was a small motor generator for radio power, plus a sea anchor, for use if the airplane was forced down.

In spite of early service troubles with the engines, the service record of the Clippers was good. Some six hours per day utilization, outstanding for that period, was achieved. Overheating caused much of the engine trouble; this was relieved when engine cowlings and cowl flaps were replaced before start of passenger service.

The China Clipper's first transpacific crossing departed Alameda on November 22, 1935, and arrived on schedule at Manila on the 29th. There was a one-day layover at Guam because of a mixup over the effect of the International Date Line. Flying time: 59:48 hours. Returning, the Clipper left Manila on December 2, and arrived at Alameda December 6, flying time: 63:24 hours, round trip 123:12. (The writer was aboard from Wake to Honolulu.)

On December 10, the Philippine Clipper left Alameda, and arrived at Manila on the 17th. After a two day delay because of a typhoon detected between Manila and Guam it left Manila at 2:43 AM on the 22nd, and arrived at Alameda on December 26th. Both takeoffs at Manila and landings at Guam and Wake were at night.

The airplane overnighted at each station. While night landings could be made, as they usually were at Guam and Wake on eastbound flights during the winter, efforts were made to get in before dark. This desire, and the relatively slow speed of the airplanes made dawn takeoffs obligatory. As a result, wake-up time for passengers was 4:30 a.m. or earlier; there was plenty of time to recover lost sleep aboard the airplane.

On its Honolulu - Alameda flight, the Philippine Clipper first had to turn back to Honolulu because of a blown spark plug on #4 engine. After taking off again, they had to shut down #1 after about 11 hours, and fly on three engines for some six hours.

The China Clipper took off for Honolulu again on the 21st, but was forced to turn back because of excessively high headwinds.

Inspection of the engine that had failed on the Philippine Clipper indicated the failure to be serious enough to arouse concern for the future. Because higher-powered engines with improved bearings had become available, it was decided to re-equip both airplanes with these 830 horsepower engines. Andre Priester then directed that each airplane accumulate 30 hours flying before next dispatch. Much of the next two months was thus spent in changing engines and conducting test flights.

One of Clyde Sunderland’s classic M-130 photos over San Francisco Bay

The China Clipper made its second crossing starting February 22, 1936. In March, two more trips were made. After the Hawaii Clipper arrived, trips were made every ten days until July, when the schedule went on a weekly basis. In all, 27 westbound and 26 eastbound proving trips were completed before start of passenger service. During this time, mail, cargo, company employees and government officials were carried. Regular passenger service started on October 21, 1936.

These long-range four engine airplanes led the way in trans- ocean transport design and operation. We see many of their contributions in the intercontinental transports of today. Martin and Pan Am showed that it could be done.