First-Hand Accounts of John Cooke, Bob Ford and Robert Hicks

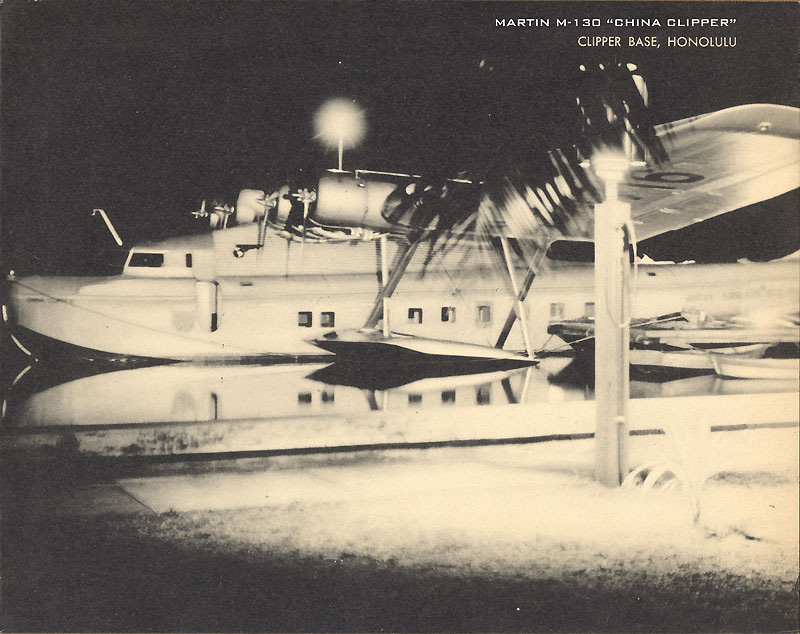

Weather and mechanical problems often affected the operations of Pan Am's flying boats. The news articles below tell a story about a rough week for the China Clipper: Trouble at sea on January 22, 1938 prompted a return to California due to motor trouble enroute from Alameda to Honolulu. Just four days later on January 26th, on the Honolulu-Midway leg of the same journey, the China Clipper again was forced to turn around, this time flying back to Honolulu due to problems with the instrument panel.

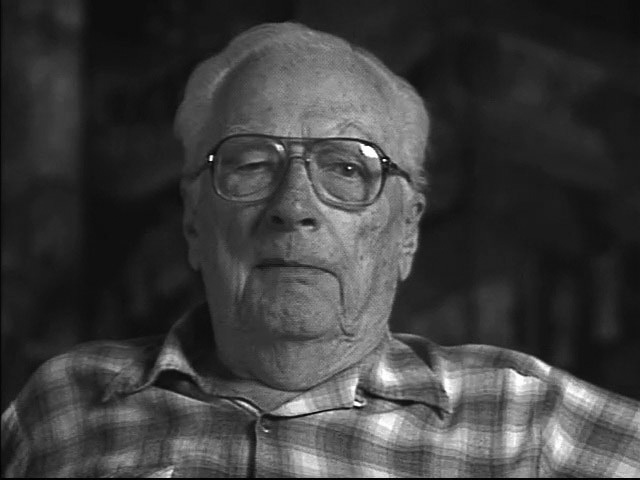

John Cooke (shown here in 1992) started with Pan Am shortly before the inaugural transpacific flight of the China Clipper as a radio operator. He moved on in the organization, serving as Wake Island Base Manager, where he was on December 8th, 1941 (Wake time), the day the Japanese first attacked Wake Island. He said this in an interview for television many years later:

John Cooke (shown here in 1992) started with Pan Am shortly before the inaugural transpacific flight of the China Clipper as a radio operator. He moved on in the organization, serving as Wake Island Base Manager, where he was on December 8th, 1941 (Wake time), the day the Japanese first attacked Wake Island. He said this in an interview for television many years later:

"Every time you took off, there was about a thirty percent chance you would have to turn back, before you got to where you were going. It was expected, either because of weather or mechanical, and the mechanical problems were usually engines, cylinders, spark plugs, something, and it was unusual to have a flight continue all the way to the destination. Not like it is today."

"Today in a jet, you take off, as soon as it takes off, you can set your watch to the time where you are going, because you know they're not going to turn back, barring a bird strike or something like that. But in those days, it was a fifty-fifty chance whether or not you were going to turn around and come home again. And we were all prepared for it, and it happened frequently, and the passengers didn't seem to mind, they just got an extra day's flight for no more money."

Bob Ford had been flying for Pan Am since 1933. Early in World War Two, not too long after he had flown his famous flight "the long way home" around the world, he was in command of another flight that didn't go as planned. Here's how he recounted that experience in an interview in 1992, also for television broadcast:

"I was flying out of Honolulu on a Martin M¬130 with a load of dependents and children of the military. We climbed up to the old Hilo intersection, and leveled off, and we were in the soup, and it was cold. It was sleeting and snowing, and zero visibility. It got rough, plenty rough. And with that single tail, instead of the three tails that the B-314 had, just that single tail, it was like a hot knife cutting butter.

"It was a rough ride. Eighteen hours later we ended up back at Honolulu where we started. The vomit was running in the aisle! Boy, it was a mess! Oh,it was a mess! I never did like that M¬130 on instruments in rough air with that single rudder!"

One more story* excerpted and edited from the "boat" days, is written by Robert Hicks, who flew as Third Officer on a wartime flight, eastbound out of Honolulu on the China Clipper.

“The China Clipper would have been lost at sea in a severe winter storm (on my 21st birthday) if the captain had not made a critical decision to turn back, nearly 13 ? hours after departing Pearl Harbor. “

“Captain Nixon had been a Navy seaplane pilot, and was said to have been a successful rum runner in the Bahamas during prohibition. One of Pan Am’s most experienced and senior flying boat captains in the Pacific Division, Nixon made some of the pioneering and inaugural flights across the Pacific in the 1930's. First Officer "Rip" Van Winkle, who had a law degree from Stanford, was hired by Pan Am after receiving his commercial pilot’s license in 1941.”

“On the flight to Pearl Harbor, as he was known to do, Capt. Nixon removed his uniform and retired to a bunk in his underwear. Behind closed curtains he might read a book, eat, or sleep, leaving the junior pilots to do all the en route flying until he returned to the cockpit to make the descent and landing. All went well, with clear weather all the way on the 17-hour and 23-minute flight.”

“Such was not the case on the return flight, when the captain ordered the plane to turn back—even though we believed we were well past the point of no return.“

“After reaching cruising altitude, Captain Nixon left the cockpit, to be called for the descent to Treasure Island. “

“The problem began about nine hours after take off. As we were nearing the forecast equi-time point, the navigator informed Van Winkle that our speed of 135 mph had decreased to 70 mph (60 knots). Van Winkle then began to plot his own fixes. With the cockpit curtains slightly open, I could hear and follow what was happening at the navigator’s table. When Van Winkle’s fixes confirmed our airspeed, the first engineer (one of Pan Am’s most senior and experienced) began telling Van Winkle that at a speed of 70 mph, our fuel would be exhausted 450 miles short of San Francisco. “

“Van Winkle, however, was relying on hourly progress reports received in Morse code from a west-bound Pan Am Boeing 314, which reported a strong 300-degrees (northwesterly) wind. Based on these reports Van Winkle seemed to believe that even though we were presently having a headwind slowing the plane to 70 mph, we would soon have a 300-degree quartering tailwind when we turned to a track of 81 degrees on the final 1,100 miles. But as the flight progressed, with fuel becoming more critical, the flight engineer began demanding that Van Winkle inform the captain. But for whatever reason, Van Winkle refused.”

“He might have believed that once past the forecast equi-time point as well as the forecast point of no return, we were committed to continue. Van Winkle appears to have erroneously assumed we were past the equi-time point, past the point of no return and expecting a tail wind we were committed to continue.”

“Soon after midnight, our speed still at 70, the sky began to become obscured by a strong winter storm moving into the Northern California area sooner than forecast. At nearly 13 ? hours from Honolulu, with the engineer shouting that he was going to call the captain out of his bunk, Van Winkle finally did call the captain. By then we were nearly three hours past our forecast equi-time point, well past our forecast point of no return, and nearly two thirds of the way to San Francisco.”

“Captain Nixon appeared in his white underwear, leaned on the navigation table to review the chart, with Van Winkle explaining his decision to continue, and the engineer exclaiming that if we continued we would be landing in a storm hundreds of miles from San Francisco.

After listening a minute or two, Nixon straightened up, said only “Turn back.” and returned to his bunk.”

“New star fixes soon confirmed a strong tailwind giving us a speed of 200 mph, for a few hours. After over 15 hours on the flight deck, Van Winkle retired to a crew bunk. Captain Nixon was notified, appeared in uniform, took the controls and made the descent and landing in Pearl Harbor after 19 hours and 40 minutes in the air.”

“As it turned out, what had happened was that an erroneous wind direction had been transmitted from the westbound B-314. With limited space on the hourly report, and for simpler transmission, only the first two digits were transmitted for each item. For example, an altitude of 7,000 feet would be transmitted correctly as 70. Similarly a 30-degree head wind should have been transmitted as 03, nearly on our nose. Instead it was transmitted as 30, which would be a quartering tail wind of 300 degrees.”

“I celebrated my 21st birthday on Waikiki Beach instead of being lost in a winter storm in the Northern Pacific Ocean.”