War Boat: The Philippine Clipper

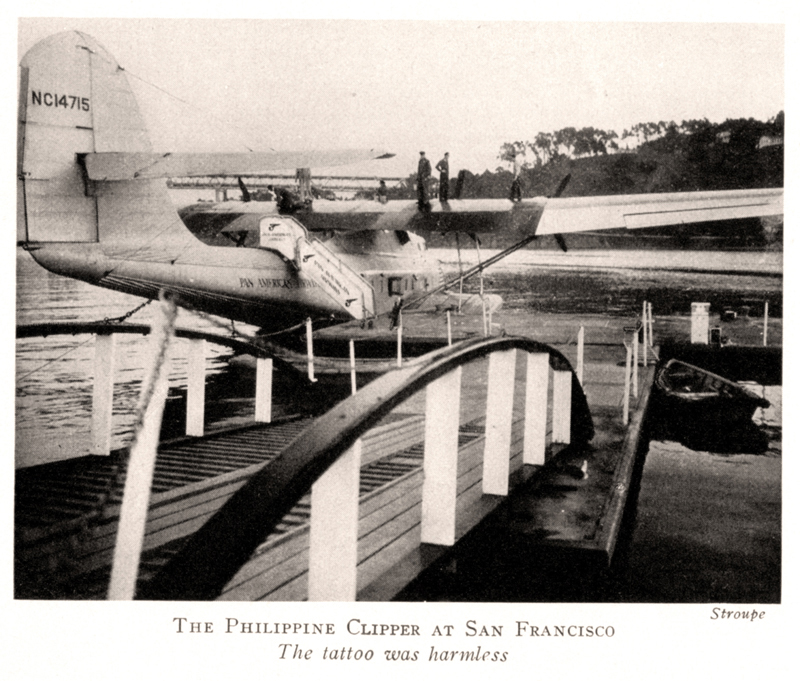

Philippine Clipper at Treasure Island, San Francisco

from “Wake Escape”/ New Horizons, January 1942 edition (PAHF Collection)

The China Clipper may have made the biggest news, being the first out of the gate into Pan American Airways’ service, when she slipped into the water for her debut public flight on Oct. 9th, 1935.

But the very next Martin M-130 to be introduced into Pan Am’s fleet from the Glenn L. Martin factory in Middle River Maryland, on November 14th, 1935 was just as stunning an addition to the fleet. She was the Philippine Clipper, NC-14715.

Any oceanic aviation was news in the mid-30’s, so the Philippine Clipper was still in headlines in coming months.

She made Pan Am’s second trip across the Pacific, leaving Alameda on December 9th, and actually trimmed over 4 hours from the scheduled round-trip time across the ocean and back. Aboard on the trip were NBC radio reporter Burt Miller, who later wrote an article for National Geographic.

The Clipper was again in the spotlight when in September of the following year she made the very first transpacific passenger trip, when Juan and Betty Trippe and a group of newspaper publishers flew all the way to Hong Kong aboard the flying boat.

And soon all the clippers settled into a relative routine, carrying important and well-heeled travelers across the Pacific, racking up millions of miles in the process. The fact that the enterprise represented an entirely new episode in human experience, with unknown risks and dangers, was made all too clear on two occasions. First in January 1938, veteran pilot Edwin Musick and crew died in a fiery crash near Samoa. Then in July of that year, the Hawaii Clipper, the third Martin M-130 in Pan Am’s service, disappeared without trace somewhere west of Guam, in a mystery that has yet to be solved.

So despite the most careful planning and maintenance, and superb training and dedication by Pan Am crews, the clippers flew across the Pacific with a certain degree of risk. As the 30’s rolled on, another danger was growing ever more clear and present: Imperial Japan.

For years since the start of transpacific service, the government of Japan, and in particular, spokesmen for the Imperial Japanese Navy, made public statements with an implied threat, about Pan Am’s flights.

Wake Island, although claimed by the United States since 1899, was technically part of the Marshall Islands, which were ruled by Japan. Further west, Guam, another US possession and Pan Am base, was the only island in the Marianas not under the control of Imperial Japan.

Even Midway Island, technically a part of what was then the US Territory of Hawaii, had once been eyed by Japan as a possible “island of interest” – as was the Hawaiian chain itself, in earlier years when Japan was first expanding the reach of its empire.

So Pan Am’s crews were not surprised to see Japanese military aircraft shadowing them as they flew near Guam in the late ‘30’s.

But wary suspicions suddenly exploded into open warfare in December 1941, when Japan attacked American and British bases across the Pacific.

It was December 8th on Wake, where the Philippine Clipper had finally got off on a regular flight to Guam after a day’s delay due to some engine trouble. It was a lucky break on an otherwise very bad day that the plane, Captain John Hamilton in command, was only a few minutes into the flight when he was summoned by radio to return to base by John Cooke, Pan Am’s base manager. Pearl Harbor had been attacked, and the country was at war! The initial idea was to have the Clipper fly a search around the atoll, but events soon intervened.

Not long after she was secured at her mooring in Wake’s lagoon, the first wave of Japanese aircraft arrived to begin the process of destruction of what would soon be known as the Alamo of the Pacific. The attackers bombed and strafed both Pan Am’s base and the Marine Corps air base that had been hurriedly reinforced with a few Grumman Wildcat fighters. The attackers left a trail of death and destruction – the “softening up” for the amphibious attack that would soon follow.

The Clipper was a sitting duck, and although she was hit with 26 bullets, none of them did any serious damage. She could still fly, and it became obvious that the plane was going to be the last way off the atoll.

A mad scramble ensued to strip her of anything not essential to flight. Out came seats, and everything else that had made the clipper a luxurious passenger plane. In the event, there was room for about 40 passengers, sitting on bare metal, to crowd onto the plane. It took three tries by Capt. Hamilton to lift the heavily loaded flying boat off the water, but it finally got away.

They flew over a group of ships, and what at first seemed a matter of relief quickly turned to dismay, as they realized those were Japanese ships headed for Wake. When they arrived at Midway after the few hour’s flight, they were greeted with the sight of fires burning – more evidence of Japanese attacks.

The Clipper made it back to Pearl Harbor the next day, to a sight of the smoking wreckage testifying to the savage attack a few days before. She then flew back to Treasure Island in San Francisco Bay, where she could be patched up and made serviceable again – this time for war work.

Philippine Clipper at Treasure Island, San Francisco

from “Wake Escape”/ New Horizons, January 1942 edition (PAHF Collection)

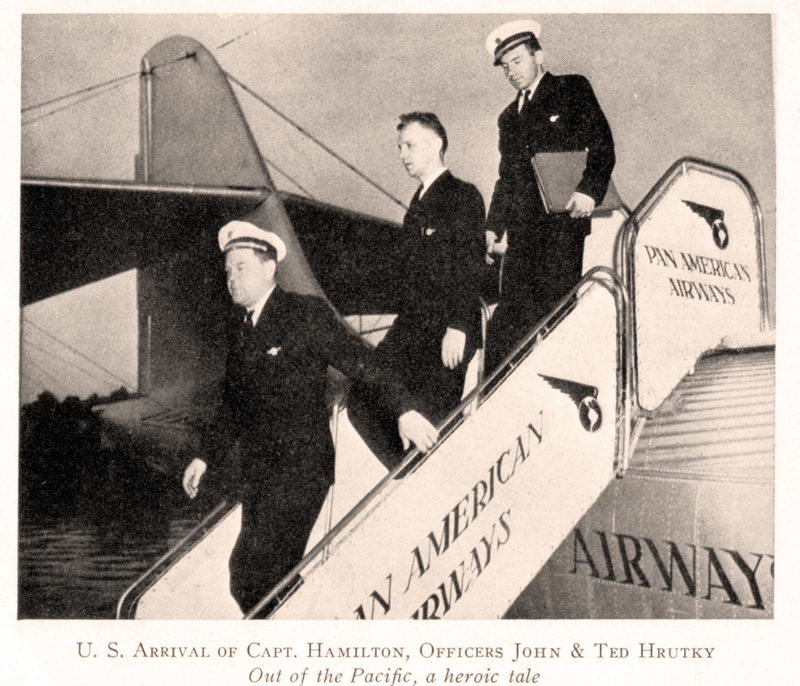

Pan Am’s own magazine, New Horizons, printed a couple of photos taken that day, with Captain Hamilton and crew disembarking, and the still-wounded clipper sitting peacefully at the dock. For the rest of her days, she would wear a “wound stripe” testifying to that day on Wake.

Like every other Pan American aircraft and employee, the Philippine Clipper would be pressed into the fight. The clippers’ routes across the mid-Pacific would end at Hawaii for the duration of the war (although Pan Am, under government contract kept flying to the Southwest Pacific). And that was an important enough job in itself, as keeping the connection to the islands was as critical a job as any.

That fact would be made fatally obvious in January 1943, and it was the Philippine Clipper that would again bear the brunt of the lesson.

The mission was an critical one. Admiral Robert English, COMSUBPAC – Commander of US submarine forces in the Pacific was scheduled to be at an urgent meeting at the Mare Island Naval Base near San Francisco. He would be bringing top-secret photographs, taken at great risk, by US submarines of potential Japanese island military targets. As with other high-level military VIP passengers, he would be flying to California on a Pan Am airplane, under contract to the Naval Air Transport Service.

So when Pan Am Capt. Bob Elzey was told by the Navy that he had to get his flight to San Francisco ASAP, he understood. He also understood that the weather along the California coast was bad – very bad. A front had stalled there, with lashing winds and torrential rains. Elzey took off from Pearl Harbor on January 20th, with every intention of delivering the admiral and his staff to Treasure Island, but the approach and minimums at San Francisco Bay made that choice a no-go on that fateful morning. There were no adequate radio aids to navigation, given wartime restrictions, and it has been assumed that the urgency dictated by Admiral English’s meeting demanded flying to an alternate landing site, at Clear Lake to the northeast of San Francisco, rather than to Southern California which was also possible. The weather precluded the pinpoint navigation that would have otherwise revealed their perilous position. Likely Elzey thought they were still over water, rather than the coastal mountains where severe winds had pushed them.

The plane never made it to Clear Lake. The Philippine Clipper, with 19 souls onboard, crashed and burned on a mountainside near Boonville, CA. There were no survivors.

The plane was lost for over a week. Military authorities, aware of the top-secret material carried by Admiral English, put up a frantic search. In the event, when the wreckage was discovered, the admiral’s photographs were not immediately found, so demolition experts set off charges on the hillside above the wreck to bury all, but only after the human remains were recovered.

The top-secret photos were eventually found, but to this day, more bits and pieces of the Philippine Clipper erode out of the hillside, in silent testimony to the sacrifice during wartime of those who were aboard, as well as the Clipper herself.