PAN AM - 1932

By Eric Hobson

JUNE

“Even Faster Air Mail”

Photo: by William C. Lazarus, Florida Memory, State Archives of Florida

18 passenger Curtiss Wright Condor biplane used by Eastern Air Transport. Florida, circa 1934. “…Top speed 142 m.p.h."

From points north of Miami, air-mail between the US, Central, and South America, took one day on rails, not wings.

But beginning June 1, 1932, demand for faster service forced the U.S. Post Office to clear Eastern Air Transport (later, Eastern Airlines) for night flights from Miami to New York City, as long as the service synchronized to Pan American Airways’ Dinner Key schedule.

Miami-New York night flights accelerated postal delivery. And in the other direction, mail headed to Havana, Cuba from New York City arrived in seventeen hours, rather than forty-one. After Colombia’s airline, SCADTA, rescheduled its system around Pan Am arrivals in Barranquilla, the typical month-long New York to Bogota mail delivery became a thing of the past.

Air mail was becoming a basic business cost throughout the Western Hemisphere, and Pan Am was key to this irrevocable transition.

“Counting Trees in Belize”

Photo compilation: Sikorsky S-38, PAHF Collection.

Bladen Nature Reserve, Wikimedia. https://commons.wikimedia.org/

"I learned more … in … two hours of flying than I could … in two months of steady ground work,” wrote Mr. J.B. Kinlock, Forest Conservator of British Honduras, in June 1932 thank-you to Pan American Airways.

Ordered to survey British Honduras’ (Belize) timber resources, Kinlock faced the mid-level bureaucrat’s too-familiar reality -- an unfunded mandate. Pan American Air Ways (Vol. 3., No. 4, p. 14), recounted that

“Airport Manager [L.E.] Sherouse heard of the difficulty and suggested that … valuable information might be gathered if a representative of the department would make the regular flight to Barrios and return at a cost of $30.60.”

Funds were approved and Kinlock stood by to fly when clear weather was forecast.

On Saturday morning, June 4, 1932, J.B. Kinlock boarded a Sikorsky S-38 for the 125 mile Belize City to Puerto Barrios (Guatemala) leg, planning to return to Belize City on the next day’s northbound flight. “Visibility was exceptionally good” on both flights and “Mr. Kinloch was able to see and identify the various kinds of timber, sketching them in on a large scale map as the flights proceeded” over terrain that is still hard to access.

“A Hot Bet on a Cold Prospect”

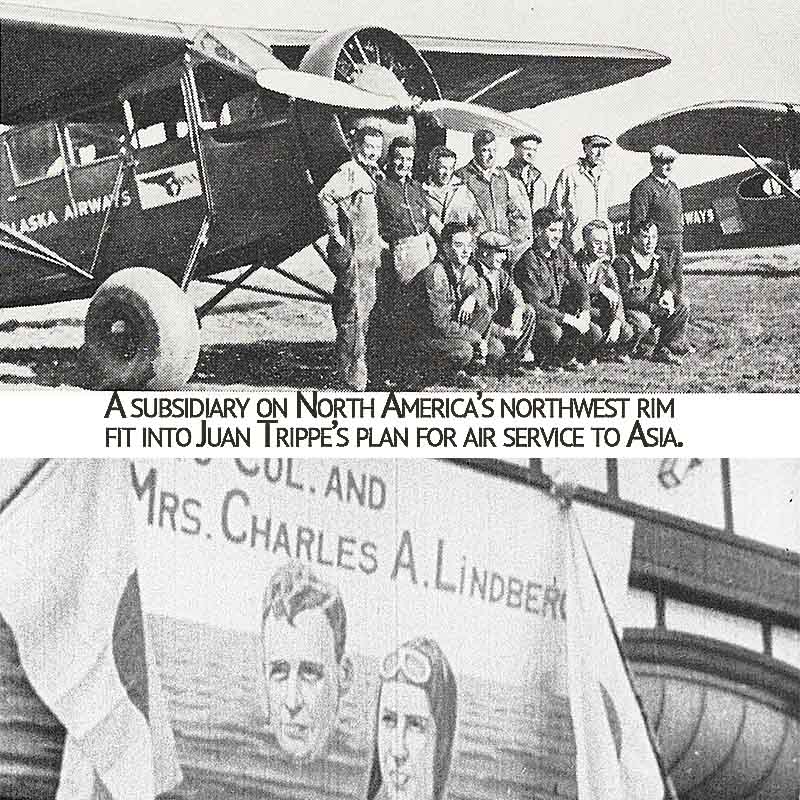

Photo compilation: 1) Pacific Alaska Airways’ ground crew with Fairchild fleet, 1932. “Clipper”, System General Office, Vol. 12, No. 9, September 1964. University of Miami Special Collections, Pan American World Airways Inc. records. 2) Still from film of Lindberghs’ Asia survey, 1931 (PAHF Film Collection).

Had they known Pan American Airways created Pacific Alaska Airways, June 11, 1932, many aviation investors would have wondered what was Juan Trippe doing. Alaska, after all, was far afield from Pan Am’s Central and South American focus.

Trippe had visited Alaska in 1926, helped finance the first attempt at air-mail service there by providing Carl Ben Eielson a WWI surplus de Havilland DH-4, and saw a viable commercial aviation business opportunity in Alaska, noting “that a Territory where people paid $400 for the privilege of walking behind a dog-sled for 20 days was a good prospect for an airline.” (Banning, "Airlines of Pan American Since 1927", p. 298.)

A wholly owned affiliate could house several Alaska operators that Trippe planned to acquire and allow Pan Am to import the operational expertise it had developed in equally challenging service environments.

A subsidiary on North America’s northwest rim fit into Trippe’s plan for air service to Asia. The prior summer (July 27 – Oct. 2, 1931) Charles and Anne Lindbergh had surveyed a potential northern circle route (Seattle to Alaska to Russia to Japan to China) for Pan Am. Although the first transpacific service bypassed Alaska, Trippe’s vision was prescient: PAA’s polar routes relied on its Alaska footprint until the development of long-haul jets.

“Record Flight”

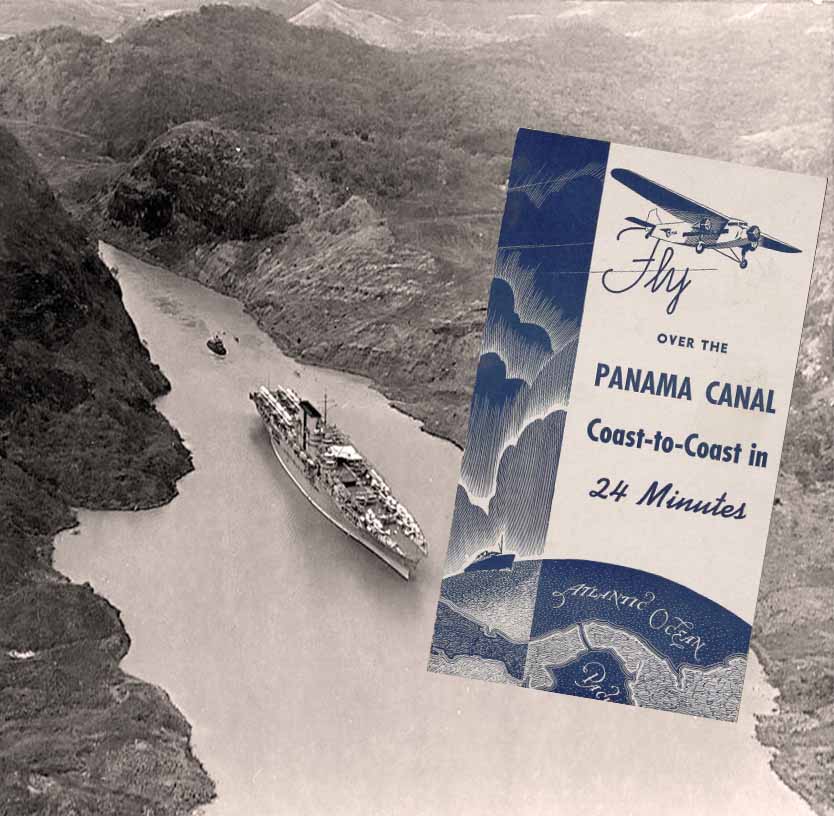

Photo compilation: 1) The U.S. Navy aircraft carrier USS Saratoga (CV-3) passes through the Panama Canal. https://commons.wikimedia.org/ US Navy, between 1928 and 1932. 2) “See the Entire Panama Canal” Brochure cover, July 1937, University of Miami Special Collections.

90 years ago, Panama and the Canal Zone -- vital to shipping-- were already an established hub of Pan Am and Panagra routes. As early as 1932, Pan Am touted a quick trip between The Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans:

“The fastest transcontinental trip on the American Continent is made by Pan American planes, flying daily between Cristobal and Panama City.” (Pan American Air Ways, July 15, 1932, p. 14).

By July 1937, Pan Am published a brochure extolling the 24 minute journey by Ford Trimotor: “See the entire Panama Canal — both the Atlantic and Pacific at one glance.

Here is a travel high-spot of a lifetime, an air cruise across the Isthmus of Panama over the Panama Canal… you step from one ocean to the other in twenty-four teeming minutes. Thrill to the sight of both oceans at one time…”

“The Curious Flock to Dinner Key”

Photo compilation: 1) Sight-seeing bus and crew - Miami Florida. By Photographer William Arthur Fishbaugh, Florida Memory, State Archives of Florida, 1930. https://www.floridamemory.com 2) Sikorsky S-40 seaplane in the water - Miami, Florida. Photo: Pan America Airways Corporation, Florida Memory, State Archives of Florida, 1931. https://www.floridamemory.com/ 3) AI-generated Sightseeing bus, 1930. Craiyon.com

Photo compilation: 1) Sight-seeing bus and crew - Miami Florida. By Photographer William Arthur Fishbaugh, Florida Memory, State Archives of Florida, 1930. https://www.floridamemory.com 2) Sikorsky S-40 seaplane in the water - Miami, Florida. Photo: Pan America Airways Corporation, Florida Memory, State Archives of Florida, 1931. https://www.floridamemory.com/ 3) AI-generated Sightseeing bus, 1930. Craiyon.com

Alongside baggage handlers, ticket agents, Customs officials, airmail processers, maintenance and flight personnel, Pan American Airways’ Dinner Key base employed an Official Guide to turn what Pan American Air Ways (Vol. 3, No. 4) described as “the constantly increasing army of visitors” from a nuisance into a marketing windfall.

The United States was a nation struck by aviation fever and, wanting to witness commercial aviation, people headed to Dinner Key in droves, even if they would never fly. So many tourists came that an enterprising Miami tour bus company ran a daily excursion to the facility.

Don Singer, Pan Am’s first Dinner Key guide reported that non-passenger foot traffic in June 1932 averaged 150 visitors a day and included “passengers from steamships stopping at Miami, convention and other groups, as well as local people and transient visitors. One of the larger groups was 280 delegates en route to a convention at Hollywood, Florida.”

Singer, and his assistants, guided the curious around the base describing Pan Am operations, extolling air travel’s virtues, and providing color commentary as aircraft landed and took off. Several times a year, Singer’s team enticed more-daring guests to buy a $3 30-minute Sunday afternoon sightseeing flight over Miami.