PAA - 1932

FEBRUARY

By Eric Hobson

"A Pan Am Transition"

Photo compilation: Dinner Key, early 1932 (Photos from Pan Am Historical Foundation collection, PAHF/Jahncke Collection and PAHF/Dunten Collection).

On Monday, February 1, 1932 all of PAA’s Miami flight schedule shifted 5 miles southeast from the four-year-old 36 St. Pan American Field to a new Dinner Key seaport.

To standardize routes and equipment, Chief Engineer, Andre Priester, sent PAA land-based aircraft to the Mexico Division and PAA affiliate airlines. The Miami-based Caribbean Division became seaplane-only, flying Sikorsky S-38’s, Consolidated Commodores and the latest in flying boats, the Sikorsky S-40s.

The Dinner Key facility was incomplete that day -- a work-in-progress, its construction team would race to complete the facility against a clock whose hands represented PAA’s ever-shifting money, effort, and schedule priorities. Service essentials (hangers, shops, and ramps) came first, so passenger amenities had to stay at the houseboat terminal.

Night fell and seaplanes nestled at Dinner Key while lights across town at PAA’s 36 St. shops burned without interruption as mechanics continued to overhaul PAA Caribbean Division engines and airframes.

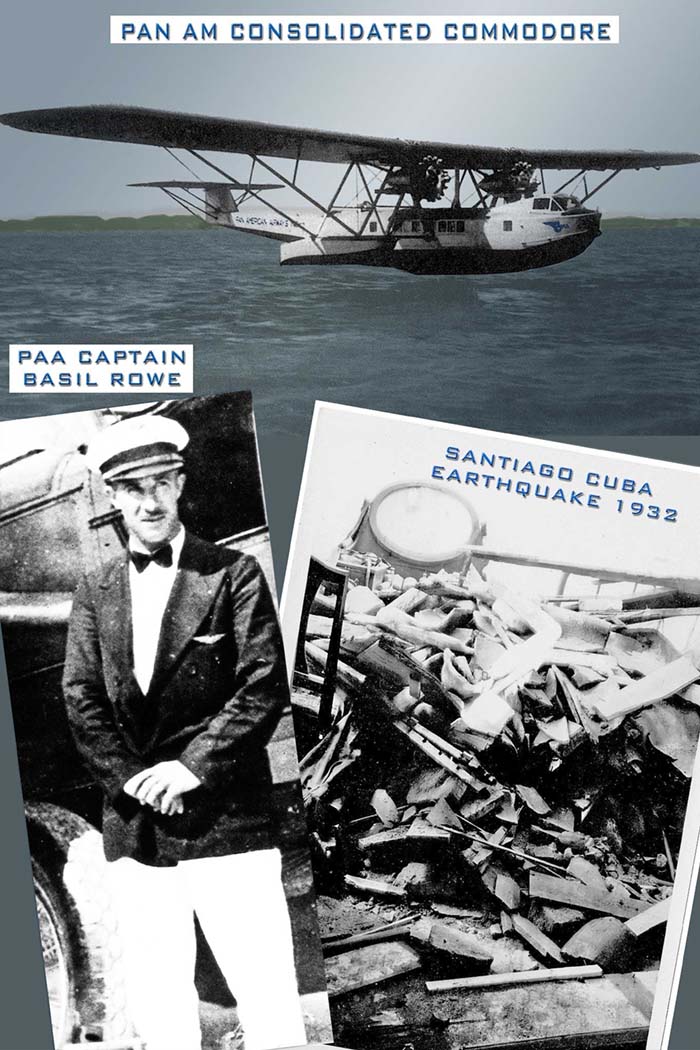

"Basil Brings Aid"

to Santiago de Cuba

Photo compilation: Basil Rowe & Pan Am Commodore (PAHF Collection) & Santiago Cuba Earthquake, 1932 (University of Miami Special Collections).

PAA Senior Pilot Basil Rowe’s 36th birthday barely registered because he was exhausted. For the past week he had flown emergency aid to Santiago de Cuba, on Cuba’s eastern end. On Wednesday, Feb. 3, the Caribbean tectonic plate wakened from a long slumber, triggering a 6.7 magnitude earthquake just south of the city. Santiago was rubble; inhabitants, including Pan American Airways’ personnel, were without a functioning hospital, firefighting/ambulance equipment, or food stores.

PAA’s Santiago de Cuba airfield and service facilities emerged unscathed because of recent upgrades, and all PAA employees soon reported to the airport. They were instructed to resume normal flight operations and to meet non-scheduled relief flights arriving as they could.

At 7:52 a.m. Basil Rowe lifted off Biscayne Bay in a spare Consolidated Commodore loaded with medical supplies and newspaper reporters. Pushing the aircraft to 100 mph and praying for a friendly tailwind to shorten the two-hour flight Rowe headed south. Meanwhile, PAA President, Juan Trippe, contacted the Cuban Government to announce these relief flights.

Two months later, Pan American Air Ways published General Machado’s response so that PAA’s entire community was included:

‘In appreciation for this service, President Gerardo Machado of Cuba sent the following radio to Mr. J.T. Trippe, President of the Pan American Airways System:

Have just received your telegraphic message at a time when the Secretaries are holding a meeting. Members of the cabinet and I express to you in behalf of the Cuban Government and people our deepest appreciation of the generous action on the part of your company in sending its plane with assistance for Santiago de Cuba.

(Signed)

Gerardo Machado’”

Source:

Machado quotation: "Pan American Air Ways", April 1932.

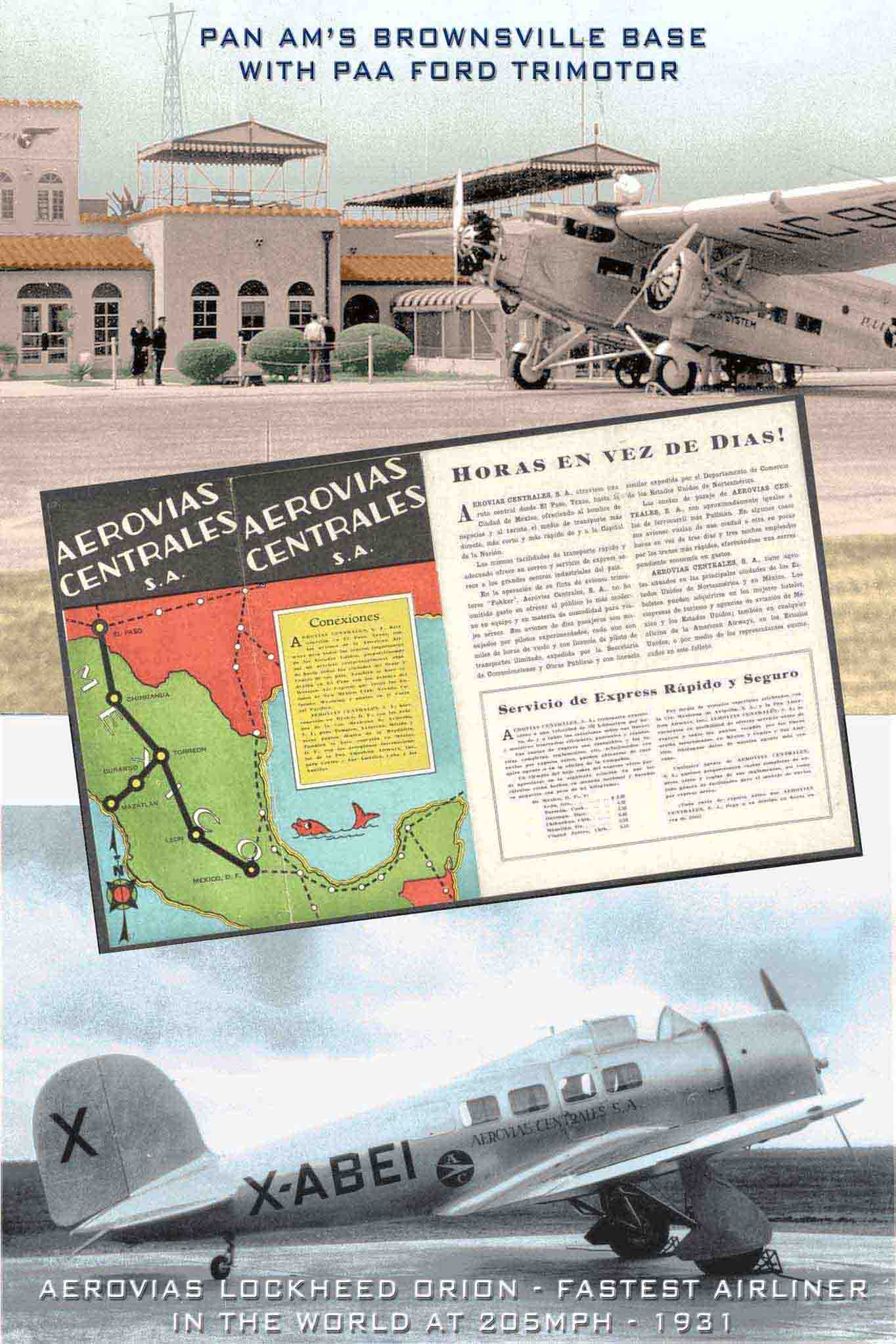

"PAA Expands in Mexico"

Photo compilation: 1. PAA Ford Trimotor in front of the Brownsville terminal (PAHF Collection) / 2. Aerovias timetable cover with map of routes, Fall 1932. (University of Miami Special Collections) / 3. X-ABEI Lockheed Orion in Aerovias Centrales SA Livery (PAHF Collection).

February 17, 1932, just as the Winter Olympics had ended in Lake Placid, NY, people at Pan Am’s New York City headquarters in the Chanin Building were planning to sign some important papers within the next week. They would create a new company — Aerovias Centrales S.A. (Mexico)— to claim Mexico’s central, inland air route,“The Aztec Trail”, following a competitor’s bankruptcy.

This corporate move would help grow and further connect Pan Am routes from Brownsville Texas, through Mexico to Central America, and reach the South American continent beyond.

In 1931, according to a compilation of customs receipts from Washington, DC, Brownsville ranked as the second most active international port of entry for passengers flying to the US with 807 planes and 3,475 passengers flying into Brownsville. Brownsville was second only to Miami which ranked as the #1 port of entry, receiving 1,480 airplanes and 12,391 passengers from international destinations.

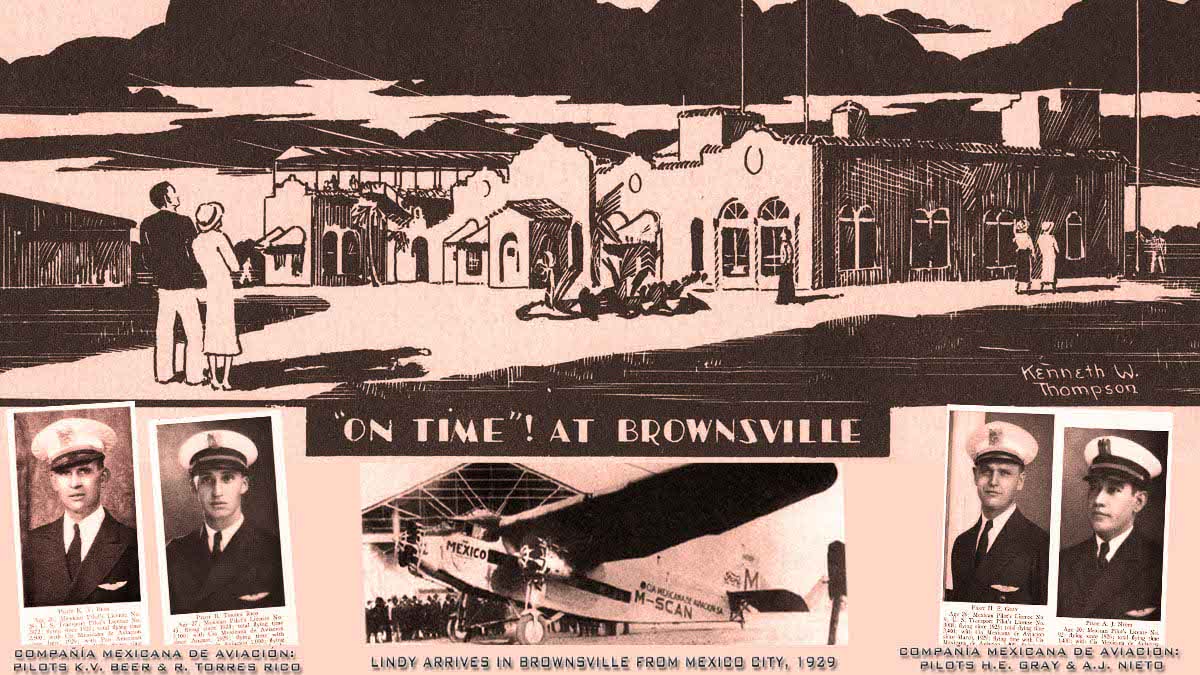

"News from Brownsville"

Pan Am had opened the route between Mexico City and Brownsville in March 1929. The plane, a Pan Am Ford Trimotor 9661 flown by aviation icon Charles Lindbergh, had been deployed to affiliate Compañía Mexicana."On arrival at Brownsville, the crowd was so large that Lindbergh was delayed 25 minutes before he could disembark..."(Gene Banning, "Airlines of Pan American Since 1927").

By February 1930 Pan Am employees had started reading “Pan American Air Ways” newsletter to keep tabs on personal news within various divisions. Given the organization’s size, and its system-wide personnel rotation, PanAmers recognized names, fretted over infirmities, celebrated successes. An issue in Nov. 1930 showed the photos of early pilots flying for Compañía Mexicana de Aviación (including a young Harold E. Gray). By 1932 PanAmers were still widely informed of personal news from Mexico: Erwin Balluder, Division Manager of the Mexican Division, had been “laid up for a week” from recurrent malaria and “is much better now.”

They learned, too, that Brownsville’s much-needed terminal remodel and expansion was complete and that Division Engineer, R.D. Sundell, had underwritten a 20-car garage at the airport. According to J. Sanchez Garza, PAAW Correspondent, “His private enterprise enabled personnel to store their cars at a $1.00 a month. Later this charge will be reduced to cover the cost of maintenance only.” Given South Texas weather, Sundell’s parking garage was fully enrolled with all 20 spots snapped up by Mexican Division pilots.

Sources:

"Pan American Air Ways", November 15, 1930, University of Miami Special Collections.

"Pan American Air Ways", April 15, 1932, University of Miami Special Collections.

"Lindy Arrives in Brownsville from Mexico City, 1929" (PAHF Collection).

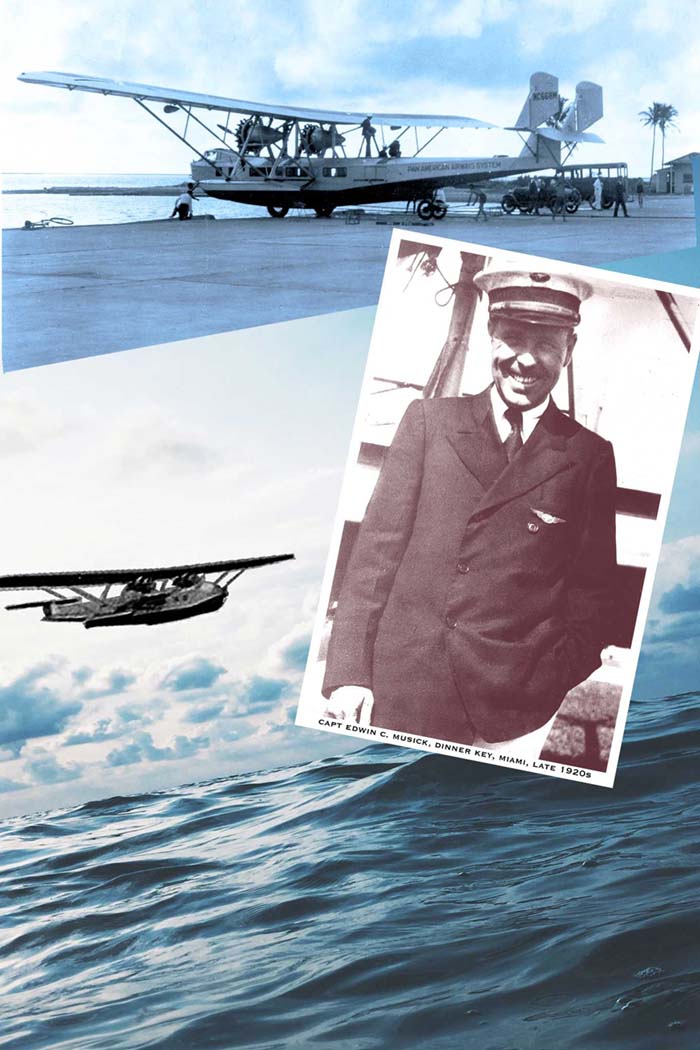

"Rescued by Capt. Musick and Crew"

Photo compilation (top to bottom): Pan Am Commodore NC668M (Pan Am Historical Foundation Collection) / "Captain Edwin C. Musick, Dinner Key, Miami, late 1920s" (R.O.D. Sullivan photo/ PAHF Collection) / Collage with Pan Am Commodore silhouette (PAHF) & "Dark blue ocean waves under a cloudy sky" by Giga Khurtsilava (Unsplash).

In February 1932, Pan Am Pilot Edwin “Ed” Musick and crew (co-pilot, James Craine, and radio operator, Eugene C. Adams), flying Consolidated Commodore, NC668M, found themselves engaged in a dramatic, personal rescue. As recorded in the "Pan American Air Ways" (Vol. 3., No. 2):

“...on the last leg of its trip from Cristobal, [the crew] sighted a capsized sloop about forty miles off the coast of Florida. A figure was clinging to its side … Musick circled … while Eugene C. Adams, radio operator, contacted the offices of Pan American at Dinner Key for permission from Customs Officials to make a landing at the scene. Permission granted, within two minutes the crew of the big flying boat was helping high school student Harold Crissy, of Miami, aboard.”

Readers learned that “Young Crissy … had gone out for a sail in the morning. His craft was caught in a squall and overturned at 11 o’clock. For five hours he had been clinging desperately with the faint hope that some other boat would rescue him. Nearly exhausted he saw the plane.”