Captain Frank E. Ormsbee:

Pan Am’s Pioneering Pilot and Union Organizer

By Eric H. Hobson, Ph.D.

Early on Pan American Airways (PAA) recruited U.S. Navy-trained pilots and mechanics. Navy veterans knew water-based aircraft, were comfortable with PAA’s by-the-book-culture, and possessed a deep-set sense of mission and of their elite status. Several Navy hires were highly decorated, including Frank Ormsbee who was entitled to display aviator wings and the Medal of Honor. (1)

Portrait of Frank Ormsbee, Pan American Air Ways Magazine, February 2, 1931 (University of Miami Special Collections).

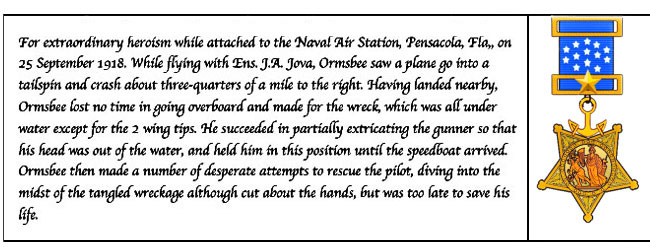

A Medal of Honor Recipient

On January 1, 1917, twenty-five-year-old Francis “Frank” Edward Ormsbee, Jr., enlisted in the U.S. Navy. He trained at Pensacola Bay Naval Air Station as a machinist’s mate and rode out World War I in Florida. Ormsbee saw no combat but became a hero for action occurring September 25, 1918.

Flying as gunner on a routine Pensacola Bay patrol, Frank alerted pilot, Ensign Jova, to an aircraft in distress as it crashed into the bay. After Ensign Jova landed nearby, Frank dove toward exposed wing tips and down to the shattered airframe. Digging into the fuselage, he pulled the unconscious gunner from the wreckage and swam to the surface and held the man’s head above water until help arrived. Handing off the gunner, Ormsbee dove into the wreckage repeatedly, tearing at it with lacerated hands in vain to extricate the pilot.

F. E. (CMM) Medal of Honor (Photo: Naval History and Heritage Command at history.navy.mil

Ormsbee’s Medal of Honor Citation

The war in Europe proved that airpower was a modern military necessity, but to expand its air wing, the Navy needed more pilots than its 1919 training program produced. Navy brass agreed to select enlisted men becoming naval aviators and Frank’s exemplary service record and maturity guaranteed him a slot.

Frank graduated third among twenty-five from the “Heavier Than Air” training that fall and, on October 8, 1920, received Naval Aviation Number N-25. (2) Over the next eight years, Chief Machinist Mate/Naval Ormsbee, amassed 2,641 flight hours (averaging 330 hrs./year) before retiring New Year’s Eve, 1928, as a thirty-seven year old Chief Naval Aviator (permanent rank).

Pan American Airways and Exploratory Flights

Frank, wife, Edwina, and children, John and Sara then moved 675 miles south to Miami, the state’s booming commercial center where they had to settle into new digs and a new environment before Frank’s new job – flying for PAA -- started Feb. 10, 1929.

With ten years aviation mechanical and eight years flight experience Frank had more than PAA’s 2,500 twin-engine-hours threshold to serve as a Senior Pilot (i.e., Captain). PAA’s need for experienced pilots on expanding Caribbean routes, meant Frank’s PAA welcome was succinct: “Glad you’re here; get in the air.” Ormsbee was issued a uniform, cleared to fly Sikorsky S-38 amphibious aircraft, added to the active-duty roster, and posted (March 1929) to the Panama Canal Zone.

This assignment was not Frank’s preference and to get him to go, PAA promised that the backwater assignment was temporary. Chief Pilot, Ed Musick, assured Frank that pilots were being hired, trained, and posted throughout the system’s periphery, and Frank would base in Miami.

Such a bargain was atypical. Usually, PAA gave orders and employees toed the line. As the company’s attempt to placate the new pilot showed, Frank Ormsbee was not typical.

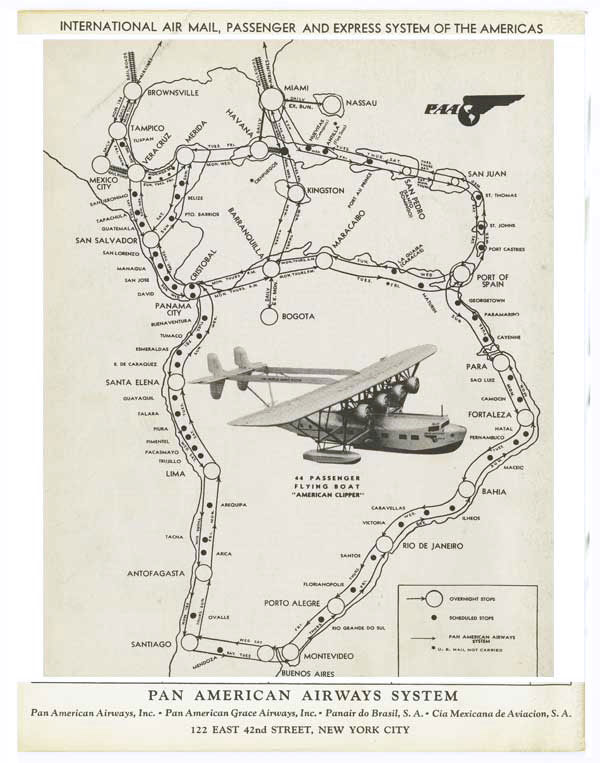

Flying for PAA differed from flying for the Navy: Frank flew longer, farther, and in more-varied circumstances. In his first eight months (March-November, 1929), Ormsbee flew 791 hours, averaging just under 100 hours per month (quadruple his 27 hour/month Navy average). Instead of routine Florida’s panhandle and Gulf of Mexico training and patrol routes, Frank crisscrossed the Caribbean and traversed Central America’s east coast and South America’s northwest coast. With few reliable maps and only rudimentary radio and navigation tools, the work was dangerous.

FAM-9 was awarded to Panagra May 17, 1929. Flying a Fairchild 71 piloted by Frank E. Ormsbee, it inaugurated flight service from Cristobal Canal Zone down the west coast of South America to Mollendo Peru. It carried US inaugural mail that had been dispatched on May 14, 1929 from Miami Florida to Cristobal Canal Zone. FAM 9 was extended further to Santiago, Chile in July of that same year.

Caribbean Route Map, from Pan American Airways, April 1932 Vol. 3, No. 2, April 15, 1932 Page 23 (University of Miami Special Collections).

A Surprise Landing

Ormsbee’s 800+ air hours during 1929 consisted of more than weekly/bi-weekly air-mail and passenger service. Much of Frank’s flying was exploratory: he refined established runs and scouted planned routes, identifying primary and emergency landing sites then assessing the logistics to establish and maintain them.

One was a coastal lagoon east of PAA’s nascent Tela, Honduras base. Unlike most emergency sites Frank added to PAA maps, Ormsbee found this one by accident…one of his own making.

In his memoir, Under My Wings (1956, Bobbs-Merrill Co.), Basil Rowe recounted ferrying empty Sikorsky S-38s from Managua, Nicaragua to Havana, Cuba after taking wealthy American doctors on a Caribbean/Central America adventure. Flying tandem above heavy cloud cover from Managua to Tela, their first refueling stop, Ormsbee, flying solo, shocked Rowe when he peeled off and dropped into a hole in the clouds. Rowe did not follow.

Basil Rowe (r)with Charles Lindbergh (l) and their S-38 (PAHF Collection).

Certain that Frank’s move was hasty (Rowe’s flight-time calculations showed neither plane near the ocean and, thus, nowhere near Tela), Rowe maintained course while his co-pilot tried to radio Frank. Hours later, the Tela station radio operator heard Frank announce he was down, out of fuel, stuck, but safe. Basil loaded 20 five-gallon cans of aviation fuel onto his plane so that he could take off at dawn to get Ormsbee aloft.

Once located, Frank recounted his ill-timed descent and the close call that followed: the ocean he expected below the clouds was a narrow gorge out of which he could not climb. Praying he wouldn’t hit a cliff wall, Frank followed the canyon’s river downstream to emerge near the ocean shoreline. Low on fuel and lost, Ormsbee landed the Sikorsky on the nearest safe-looking body of water. He needed to calm down, assess his situation, and radio for help.

Storm Clouds over a Sikorsky S-38 (PAHF, Jahncke Collection).

Frank tapped his telegraph key but got no replies because the aircraft’s hard antenna was range limited. Eventually a man of Mayan descent appeared paddling a dugout canoe across the lake. Frank, using pantomime and what little Spanish his visitor understood, asked the man to unspool his aircraft’s trailing radio antenna. Added length allowed Ormsbee to send the S.O.S. transmission that Basil and PAA personnel heard one-hundred miles west.

Refueled, and his Honduran assistant richer by several dozen cigarettes, Frank and Basil lifted both aircraft off the lagoon and wing-waggled farewell to the man in his roughhewn watercraft. Frank’s story spread through the PAA pilot’s corps and the new emergency site was fondly labeled “Redskin Lagoon” in homage to Frank’s unnamed Honduran ground crewman.

Pioneering Air Mail Service to South America

Few air mail/passenger lines that Ormsbee scouted were as important as the service from Miami through the Panama Zone and down South America’s western coast. Frank’s familiarity with the route’s Caribbean section, his amphibious aircraft experience, and his ability to represent the company to local governmental officials, led PAA to tag Frank to initiate the Miami to Santiago, Chile service on July 16, 1929. For the inaugural mail-only flight, Ormsbee flew from Miami to Cristobal, Panama (Miami-Havana-Cancun-Belize City-Tela-Cristobal) in Sikorsky S-38 NC8020. (3)[1] At Panama, he rendezvoused with a Panagra Ford 5-AT Tri-motor and transferred his southbound mail as photographers recorded the event.

Frank Ormsbee (right) with Donald Duke and Gerald Bliss: "First receipts to Postmaster for First Air Mail on longest Air Mail Route in the World – Cristobal Canal Zone to Santiago Chile, F.A.M. No. 9 connecting at Cristobal with direct air mail routes to United States, Canada and Mexico. 8:00 a.m. July 16, 1929" (University of Miami Special Collections).

A Crash in Colombia

With PAA’s South America western mail service established, many Central American route kinks smoothed out, and more pilots cleared to fly, Frank returned to established Caribbean routes.

Frank’s no-crash luck ran out November 6, 1929 when a bird struck the windshield of the Sikorsky S-38 (NC9137) (4) he was flying near Barranquilla, Colombia and his plane went down. Ormsbee walked away with cuts, bruises and a broken nose. Luckily the flight carried no passengers and his co-pilot/mechanic survived.

Accident investigators faulted Ormsbee and grounded him for thirty days (5) yet, citing Frank’s exemplary record, they recommended that PAA return Frank to Miami so that he could resume flying as soon as the penalty period lapsed. Having averaged 100 flight hours/month since March, no one in the Ormsbee family was going to challenge a thirty-day vacation.

Piloting an Elite Caribbean Tour

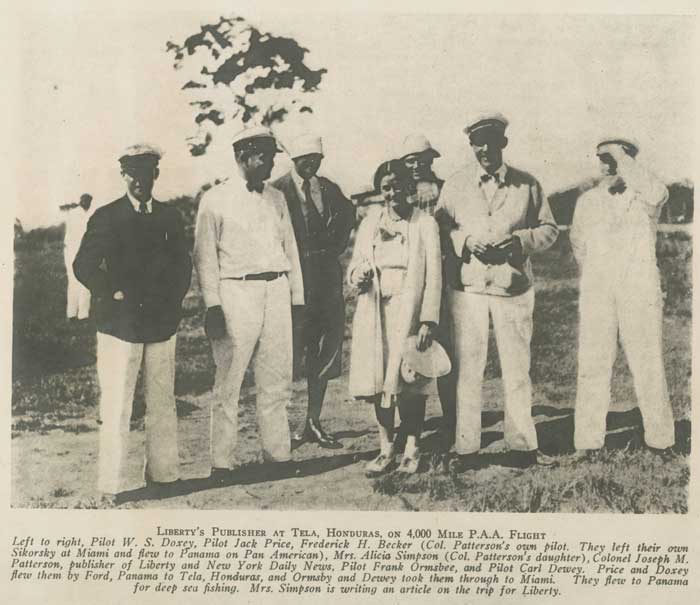

A rested Frank slipped into the left-hand cockpit seat to begin 1930 with a high-profile charter assignment. Col. Joseph M. Patterson, millionaire publisher of New York Daily News and Liberty Magazine, and his daughter, Alicia Patterson Simpson, contracted PAA to fly the Patterson group round-trip Miami to Panama for deep-sea fishing. Patterson’s retinue included his own pilot, who had flown Patterson’s Sikorsky from New York to Miami. From that point, PAA staff took over; Ormsbee flew the group across the Caribbean to Pela, Honduras, and onto a PAA-crewed Tri-motor Ford.

PAA’s Director of Communication, William Van Dusen, who lauded PAA’s high society connections, placed a Patterson entourage-PAA pilots photo in the February 24 Pan American Air Ways in-house newsletter with acaption announcing that Mrs. Simpson was writing an article about the adventure for Liberty Magazine. The publication boasted the nation’s largest magazine circulation and promised PAA a national spotlight.

Liberty's Publishers at Tela, Honduras, on 4,000 Mile PAA Flight. Frank Ormsbee, Pilot (2nd from right). Photo: Pan American Airways, Vol. 1, No. 1, Feb. 24, 1930, p. 5 (University of Miami Special Collections).

One month later American Air Ways readers learned that Mrs. Simpson’s five-page Liberty Magazine article, “Deep Sea Fishing in Panama,” appeared March 29, 1930, and contained, “Fourteen pictures and a map of the Pan American route to the Canal Zone.”

Looking for Mayan Ruins

1930 ended with Ormsbee assigned another high-profile charter, piloting archaeologists who hoped to locate forgotten Mayan cities. The Central American Expedition of the University Museum (University of Pennsylvania), led by millionaire Museum Trustee Percy Madeira left Biscayne Bay Tuesday afternoon, December 2, headed to Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula. For twelve days, Captain Ormsbee crisscrossed the Yucatan on thirteen survey flights. (6)

Frank’s passengers learned that spotting Mayan ruins beneath dense canopies was challenging, and aerial surveying was harder than hoped. Madeira reported that Ormsbee’s tree-top flying and the tight banking was “too hard on the nerves to continue for more than a limited space of time” and that the engine noise was deafening. Still, Madeira marveled at commercial aviation travel realities. “At 6 o’clock in the morning of the previous day,” he wrote, “we had broken our camp in the heart of the forest of north central Guatemala, and…36 hours later…we were comfortably settled in the Columbus Hotel in Miami, Florida; a most extraordinary transition, possible only with a modern airplane as the magic carpet.”

Pan American Airways-Penn Museum Expedition, 1930. Source: Madiera, P.C., “An Aerial Expedition to Central America.” The Museum Journal 22.2 (June 1932): pp. 93-154. The Personnel and the Plane, at Miami, Florida. Left to right – Dr. J. A. Mason; William Carey, co-pilot; Frank E. Ormsbee, chief pilot; Robert A. Smith; Percy C. Madeira, Jr; Gregory Mason.

Campañía Mexicana de Aviación (CMA)

Ormsbee’s life was mostly routine by 1931. Following the crash in Colombia, he flew 961 flight hours representing a less-grueling 64-hour/month average.

Still, he endured another unwelcomed posting to PAA’s service perimeter, sent to PAA affiliate Campañía Mexicana de Aviación (CMA) for the first part of 1931 to bolster its senior pilot numbers during a time of rapid growth. One benefit of this assignment was the opportunity to accumulate hours in land-based aircraft.

His CMA colleagues welcomed Frank and sought his advice about job security and work safety. In his memoir, Pan Am Pioneer: A Manager’s Memoir, from Seaplane Clippers to Jumbo Jets (1995, Texas Tech UP), PAA Executive, Sanford B. Kauffman, recounted how CMA’s American pilots feared losing their jobs as Mexican pilots gained the flight hours and credentials needed to assume aircraft command. To secure Mexico’s airmail routes, PAA promised to employ Mexican nationals at all operational levels.

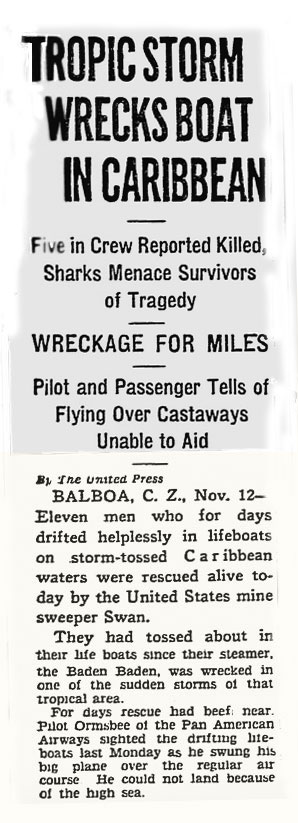

Another Rescue

By Fall 1931 Frank was flying PAA’s Caribbean Cut-off Route (Miami-Havana-Kingston-Barranquilla-Cristobal) and the Kingston, Jamaica’s newspaper, The Daily Gleaner, tracked his bi-weekly arrivals and departures in Consolidated Commodore flying boats. Most of these flights were uneventful. Still, twelve years after his rescue of a navy gunner in Pensacola Bay, Captain Frank Ormsbee became involved in another life-saving ocean rescue.

Airborne on Monday, November 9, following a two-day severe-weather delay on the northbound half of the Miami-Panama run, Frank spotted small boats foundering in the heavy seas north of Barranquilla, Colombia. Ormsbee turned the Consolidated Commodore (NC667M) on a long, slow decent and backtracked for a closer look.

Pan Am Commodore in Flight (PAHF, Matthay Collection).

Sailors from the schooner, Baden Baden, had abandoned the sinking ship hours earlier. Five men drowned in the escape, and eleven others, including its captain, assumed they would not survive long. Then they heard aircraft engines. The Commodore’s return and fly-over confirmed that they had been spotted.

Ormsbee did not land, however. Although the Commodore could accommodate all eleven, landing amidst the high swells guaranteed that no one – aircrew/passengers or ship crew-- would survive. Ormsbee radioed coordinates to PAA radio operators and broadcast an appeal to all ships in the region to come to the survivors’ aid.

Captain Halder, of the Baden Baden, reported that “We had no hope when we went over the Baden Baden’s side of making land in the lifeboat. This gave place to visions of quick rescue when a plane flew over us Monday. We waved to the plane and were certain we were seen. When aid did not come for two days we began to despair.” By the time the U.S. Minesweeper, Swan arrived the two life boats had drifted further into the western Caribbean, about 50 miles north of Cartagena.

News story of Ormsbee’s discovery while flying in a Caribbean storm. The Pittsburgh Press - Nov 12, 1931.

Ormsbee's Labor Organizing

Eight months later, Francis E. Ormsbee was missing from the 48-man Senior Pilot roster published in Pan Am Air Ways (July1932). Frank had carried out every flight assigned to him during three and one-half years with PAA and more than once risked his life to do so, yet 41-year-old Ormsbee was not flying for PAA. He had left Pan Am.

A close-up of Frank Ormsbee (Photo: Congressional Medal of Honor at CMOHS.org).

Pan American Airways (PAA) growth precipitated pilot shortages in 1931 and, even amidst a hiring binge, PAA struggled with staffing as the company lost pilots to accidents, health issues, and competitor poaching. Few new hires had the 2,500 multiengine hours PAA Chief Engineer, Andre Priester’s required for over-water command, so new hires usually flew in the right-hand seat. High-flight-hour pilots with land-and amphibious-aircraft clearances like Francis “Frank” E. Ormsbee were essential to bring new hires up to PAA command requirements.

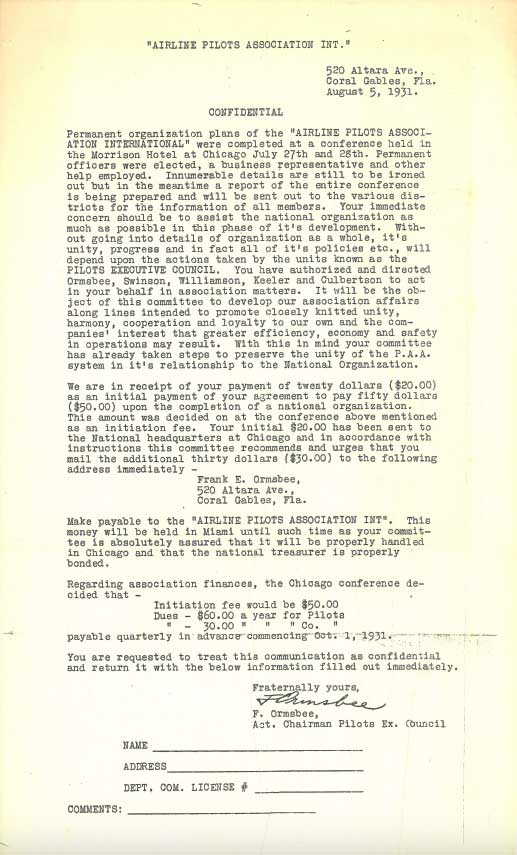

PAA leveraged Ormsbee’s skill and Medal-of-Honor hero status for over three years, assigning route-scouting missions, route inaugurations, and high-profile charter flights, all accomplished with only one close shave in Colombia in 1929. But, by summer 1931 PAA brass heard the news: Ormsbee was spearheading pilot unionization efforts via the new Airline Pilot’s Association (ALPA).

Ormsbee, ALPA charter member #6, attended the inaugural ALPA meeting at Chicago’s Morrison Hotel, Monday and Tuesday, July 27 & 28, 1931. Headed home to Miami, Frank composed a confidential memo to all PAA pilots informing them of ALPA’s establishment and summarizing activity that he (Acting Chairman of the five-member PAA Pilots Executive Council, working with Casper D. “Cap” Swinson, Stanley J. “Red” Williamson, Roy E. Keeler, and Wallace D. Culbertson) had carried out on their behalf.

Ormsbee Memo to ALPA August 5, 1931 (PAHF Banning Collection).

Ormsbee Memo to ALPA August 5, 1931 (PAHF Banning Collection).

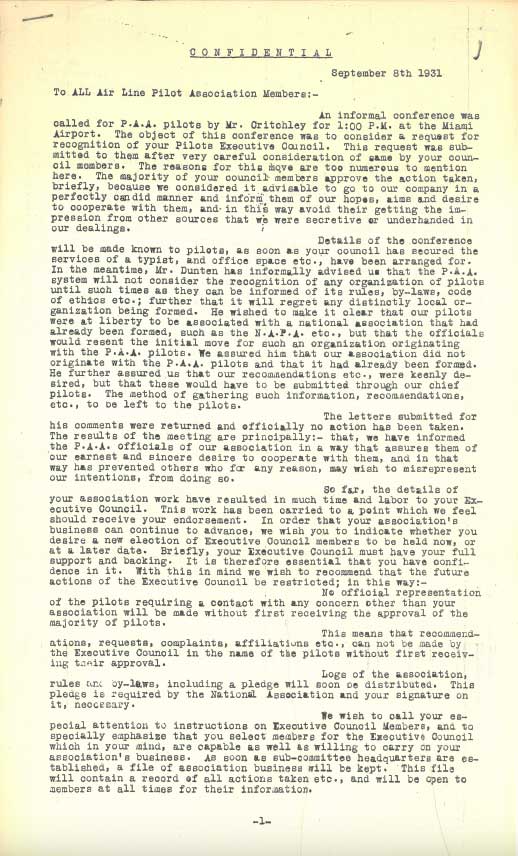

One month later PAA pilots received a summary of a September 8 meeting with Edward Critchley, Miami Operations Director, requesting recognition of the PAA Pilots Executive Council. Ormsbee explained that the council members “considered it advisable to go to our company in a perfectly candid manner and inform them of our hopes, aim and desire to cooperate with them, and in this way avoid their getting the impression from other sources that we were secretive or underhanded in our dealings.”

Ormsbee told his colleagues that the meeting with Ed Critchley and Roscoe Dunten (Chief, Caribbean Division), was cordial, but “The letters submitted for his (Critchley’s) comments were returned and officially no action has been taken.” Critchley’s silence reflected PAA anti-labor stance: PAA did not welcome unions under any pretense or in any shape. Unions threatened the industry’s labor advantage and PAA intended to keep this power.

Captain Roy Keeler, who joined PAA in 1929 claimed “The operators fired at the drop of a hat.” Talking to aviation labor historian, George Hopkins, in his history of ALPA, Flying the Line: The First Half Century of the Air Line Pilots Association (1982, Airline Pilots Association), about challenges faced in the early 1930s, Keeler described a too-frequent conundrum:

“The operators always talked safety. Juan Trippe and [Ed] Musick, sure they wanted it. But they had short memories, and when things would go along well – no accidents – they’d forget. ‘Just a little line of thunderstorms,’ sure. They’re not flying it. But you’d better go if they said so.”

Schedule adherence over safety, known as “pilot pushing,” is credited with many pilot (and passenger) deaths and firings when a pilot resisted orders to fly against professional judgment. Without representation no pilot flying for a United States airline could fight an employer’s actions and ALPA’s efforts to support fired pilots rarely succeeded because, as historian Hopkins admits, “ALPA was still too weak to contest every dismissal from an airline.”

Ormsbee’s mobilization efforts gained momentum and PAA responded. The message from New York was draconian and unambiguous: even Medal of Honor recipients are replaceable. Although two dozen PAA pilots were ALPA charter members, Frank was identified as the lead, and was terminated as an example. (7)

Although the termination was discombobulating, it was not a professional death knell for forty-one-year-old Ormsbee. Dave Behncke, ALPA founder and president added Frank to his Chicago staff. According to Kauffman, Behncke planned on “using his war-hero status to good advantage and fighting with Pan Am over his reinstatement.” While Behncke failed to get Ormsbee reinstated, Kauffman argues:

“the Ormsbee affair proved that APLA could play the game of public relations, and it forced Juan Trippe to do some artful dodging to defuse the criticisms of pro-labor congressmen and senators. Trippe learned more quickly than most airline executives that tangling with ALPA was potentially dangerous.”

Ormsbee -- intelligent, well-spoken, strategic -- read commercial aviation’s future and foresaw this economic sector’s short- and long-term financial and political power. Hopkins argues that Frank Ormsbee “was the first to suggest, among other things, that the locus of ALPA’s activities in the early 1930s should be Washington, not futile and dangerous strike confrontations spread across the country. He also argued from the very beginning that ALPA should concentrate on securing a pilot’s amendment to the Railroad Labor Act of 1926.”

ALPA sent Ormsbee to Washington in early 1933 where he assessed ALPA member needs and contract-leverage points, monitored national sentiment and identified Congressional lobbying opportunities. He was so effective that many pilots preferred Frank over Dave Behncke as permanent union president. Because Ormsbee was a man whose “powers of intellection, persuasion, and analysis were formidable,” Hopkins states Ormsbee threatened Behncke’s power and prestige.

Dave Behncke’s brash exterior hid a thin skin and fear of usurpation, and after one year at ALPA, Frank was again unemployed. Behncke fired Ormsbee in early 1934 on what historian George Hopkins describes as jealousy-based “trumped-up charges of ‘conduct unbecoming a member’.” Hopkins also points out the oddity/illogic of the charge, noting that “Ormsbee was not technically a member of ALPA, since he no longer worked for PAA.”

Frank’s unexpected availability benefitted the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Air Commerce which offered Ormsbee its Assistant Manager of the First Air Navigation Division position with duties that included serving as an Inspector/Patrol Pilot. Stationed in Fort Worth, Texas, Frank monitored commercial air routes across the country’s middle southern tier.

There, flying solo on the final leg of a routine inspection tour from Oklahoma City to his operational base in Fort Worth, late afternoon, October 24, 1936, Ormsbee encountered severe thunderstorms. Just north of Ardmore, Oklahoma, the storm overtook Frank as he tried to find the nearby airstrip. Enveloped in weather that left him “flying blind,” Frank, a skilled instruments-rated aviator, flew into a hillside. The forty-four-year-old died on impact and his family took his body eastto the Ormsbee family home in Pawtucket, Rhode Island for burial.

Only in 1945 -- nine years after Frank Ormsbee’s death -- did PAA sign a labor contract with ALPA, the next-to-last major US carrier to do so. Immense pressure from Washington, mixed with company calculations related to Truman administration post-war commercial and air-mail route re-apportionment drove the union-averse organization to enter into an ALPA contract.

Ormsbee Correspondence to ALPA and ALPA Agreement,1945 (PAHF Banning Collection).

Frank Ormsbee’s name did not appeared again in a PAA publication until a July 1958 The Clipper feature article celebrating flight mechanic John E. Donahue’s thirty-year PAA anniversary.

Framing Donahue’s career from mechanic, second rate, to chief cargo inspector in Miami (and jobs in between), the Clipper staff writer returned to the company’s earliest days, when, “As a flight mechanic, Donahue flew with such old-timers as Captains Musick, Basil Rowe, and Frank E. Ormsbee.” Reaching for the obligatory humorous anecdote, the uncredited writer added:

Donahue recalls a Managua city official, speaking at a luncheon following a survey flight across Nicaragua, who marveled at Ormsbee’s ability to fly across the mountainous country without getting lost.

Ormsbee replied, according to Donohue: “It’s easy, we just drew a straight line and followed it.” A little later they took off from Managua on the return flight to Miami – and got lost, 300 miles off course.

Ormsbee’s final PAA appearance was twenty-three years later (1981) in the Pan Am Clipper. Juxtaposed beside an announcement of PAA’s service to Phoenix, was the photo taken in Cristobal, Panama, July 16, 1929, at the inauguration of PAA’s FAM 9 service to Santiago. With southbound airmail bags at his feet, Frank Ormsbee leans on Sikorsky S-38’s (NC8020) right pontoon and looks into commercial aviation’s future.

Footnotes

(1) Ormsbee’s PAA colleague, Capt. William L. Elmore, received the Navy Cross for heroism while aboard a US Navy submarine during World War I.

(2) This class contained other future PAA pilots: Arthur “Mike” E. LaPorte, William L. Elmore, and W.A. Cluthe.

(3) Sikorsky S-38 (NC8020), the 4th S-38 off the assembly line, was PAA’s first purchase of this important aircraft.

(4) Sikorsky S-38 (NC9137), had four months of flight service, delivered to PAA June 30, 1929. (Davies, 13) Patched up it flew for PAA through 1935.

(5) One wag, reflecting on the investigators’ blame assignment, observed that for the investigating team to find Ormsbee at fault, “the bird must have filed a flight plan.”

(6) For more on Frank Ormsbee’s work with the Central American Expedition of University Museum, see “Eyes in the Sky: Charles Lindbergh & the Birth of Aerial Archaeology” https://www.panam.org/take-off/733-eyes-in-the-sky

(7) PAA pilot, Roy Keeler, elected as an ALPA vice-president at the union’s 1932 convention in Chicago, flew with PAA from 1929 until he retired in 1960.

Works Cited

Davies, R.E.G. Pan Am: An Airline and its Aircraft. Middlesex, England: Hamlyn, 1987.

“Donahue Completes 30 Years in Latin American Division.” The Clipper, Vol. XV, No. 7 (July 1958): p. 3.

Grandt, Robert. Skygods: The Fall of Pan Am. New York: William Morrow & Co. 1995.

Hopkins, George E. Flying the Line: The First Half Century of the Air Line Pilots Association. The Airline Pilots Association, Washington, D.C., 1982.

Kauffman, S.B. Pan Am Pioneer: A Manager’s Memoir, from Seaplane Clippers to Jumbo Jets. Ed. George Hopkins. Lubbock, TX: Texas Tech UP, 1995.

Ormsbee, Francis E. Correspondence. PAHF Archives.